To Save a Country

by

George Patterson

|

|

To Save a Country by George Patterson |

Long Riders are a unique group of humans. They set off to explore the world on horseback for a variety of reasons. Adventure. Science. Even religion.

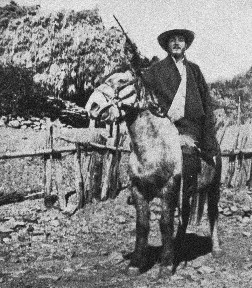

One such unusual case involved a young Scotsman. It was 1946 when George Patterson received a clear command from God. The 26-year-old factory manager was to go to Tibet and proclaim his Christian faith to the local populace. Of course there were a few minor problems. George had never been out of his native land, spoke no Tibetan, and had no money. But what the young Long Rider did have was LOTS of faith.

The tale of George's travels, first across war-ravaged China and then into the mysterious mountain kingdom of Tibet, is a moving account alternately full of spiritual insight and hair-raising adventure. It is a grand and moving story. Yet this much we can say. Against all odds the young Scot became a medical missionary, learned fluent Tibetan, and adopted the customs and manners of his mounted hosts so completely as to become nearly "Tibetan" himself.

It was because of the amazing emotional confidence placed in him that the Tibetan leadership entrusted the young Long Rider with the entire fate of their wind-swept kingdom. In January, 1950 word reached Tibet that the Chinese Communist army was preparing to invade and conquer George's adopted homeland. Winter had set in and all the traditional passes were closed. There was only one option and it entailed crossing the Himalayas, during the height of winter, over a pass that no one had ever attempted.

The mission was tantamount to suicide. But if George had one thing on his side, it was unwavering faith that God had sent him to Tibet for a purpose. With that conviction lodged firmly in his heart, he saddled up his horse, "who was built like a song and moved like a melody", then set off into a winter wasteland.

2nd

February

Lawo to Samba Druca, Tibet

The

stage for today was to be a long one, and so we took sufficient food out of the

boxes to carry in our saddlebags as a snack.

As we were leaving with our caravan today it meant that we would arrive

ahead of them, and would have to wait until they arrived with the loads before

we could have a proper meal. This

was where I appreciated the tsamba and dried meat.

For no matter how sustaining porridge and the like might be in the

civilized West, I had found such food insufficient during my travels in Tibet.

The high altitudes, the rarefied atmosphere and the constant exercise

created a tremendous appetite a few hours after the heaviest meal of bread or

potatoes or porridge, and with the prospect of another six or seven empty hours

one lost one’s confidence in Western conceptions of food values.

Thus I had come to prefer the nourishing monotony of tsamba and dried

meat rather than the unsatisfying variety of Western food;

further, there were insuperable difficulties in the supply and transport

of the latter. With two or three

bowls of tsamba and a handful or two of dried meat dipped in pepper tucked away

inside me, and a supplementary lump of tsamba and a few pieces of dried meat

tucked away inside my gown, I was ready to face the elements and the future;

and thus it was on this day and occasion.

I

was now back on my own bay, having sent back Dege Sey’s horse with his groom,

and with this reminder that all trimmings were past I settled down to the grim

journey ahead.

Almost

immediately we were reminded of just how grim the journey was going to be when

the trail led suddenly into the dry bed of a river. At first there was a trickle of water among the stones but

gradually this died out and we were left in remarkable surroundings.

The valley had narrowed until there was no room on either side of the

river for even a trail over which a horse or man could go.

The place must have been completely impassable when the river was in

spate: now what little trail there was disappeared in the course of

the river and appeared at times among the small stones and huge boulders of the

river bed, and the horses picked their way with the greatest difficulty.

The sides of the mountains were so steep that no sun entered at this time

of the morning, adding to the already eerie character of the gorge.

When the muleteers let out an occasional yell at a horse or mule or yak

which wandered to the sides in search of grass, the sound seemed to rise in a

diminishing spiral until it escaped over the tops of the distant mountains.

| I learned to ride without

hands, swinging left and right on a madly-galloping horse while dipping

earthwards to pick up stones on the ground, using my knees only to grip

the horse. I learned to ride up and down steep, narrow trails, in

mountain races where nerve as well as skill was necessary to stay alive,

as the mad Tibetan riders drove their horses past each other on

precipitous ledges above sheer drops of thousands of feet George Patterson |

|

It

must have been about three hours later when we found a path leading out of the

river bed, which was by that time beginning to fill up with water from some

invisible source. I had been

growing more and more anxious as the boulders grew in size, towering above us,

and the water rose gradually all round us gurgling ominously in that gray

half-light as it met resistance from the stones.

However, just when it appeared that we might have to retrace our steps,

the water now swirling about the horses’ knees, a faint path appeared on the

left bank and snaked its way up the sheer side of the mountain.

We followed this trail over the high shoulder of the mountain, still

keeping that menacing gorge under our stirrups until we were two or three

thousand feet above it, when it dipped into a hollow and led to a few scattered

houses. The unconscious strain of

that journey must have been tremendous for when Loshay suggested a short stop

for tea I felt a surge of relief which was almost physical in its impact;

the others showed it too in an exaggerated belligerence and impatience

with the startled villagers.

We

waited until the pack animals had caught up with us, and then, having checked

the loads, which had received a severe knocking-about among the boulders in the

river, we took to the trail again. The

shoulder of the mountain had flattened out somewhat to form a sheltered

declivity in which the houses nestled, but the sound of the river from that

forsaken gorge could still be heard. Once

the end of the declivity had been reached we descended sharply again, and I

received another rude jolt. For an

almost identical gorge was unfolding itself before me but this one had to be

crossed by bridge – and what a bridge! The supports (excuse the term!) of this contraption consisted

of roughly trimmed logs laid crosswise on each other to form the tapering sides

of a tower-like structure on either side of the gorge, in much the same manner

as we built houses of matches when we were children, and these were spanned by

two trees from which the branches had been trimmed and over which some boards

were loosely tied by creepers. Underneath

this appalling sight there was not even sufficient water to make a probable

landing bearable, only the gray nakedness of giant boulders leering up at us

invitingly. Well, it had to be

crossed. Fortified by a deep

breath, several bowls of tea and a – comparatively! – blameless youth, I

recklessly lunged forward wishing fervently I had had tennis shoes instead of

heavy riding boots as I felt the boards move uneasily beneath my feet.

Now to cross that structure alone would have been a superb feat for an

iron-nerved trapeze artist, but when one had to lead a horse across it as well

it became a nightmare (and I hope you’ll pardon the unintentional pun).

I do not know what the horse felt like but if outward appearances were

any criterion then I reckon we were the two biggest hypocrites in the animal

world at that moment, for my apparent sang-froid was excelled only by the

horse’s. I had horrible memories of a similar occasion when, in

negotiating a “bridge,” a friend’s horse had slipped down between the boards

on a wildly swinging suspension above a raging river in the dark.

I was ahead and could not move forward, Geoff was behind and could not

move at all. The memory of that

horrible night will haunt me forever – and it haunted me now.

I had a confused idea that I was being unconsciously sacrilegious as I

got mixed up in my prayers for myself and the horse;

but this was understandable, since I was not sure whether to hold on to

the horse if I slipped, or hold on to the horse if he slipped.

And then, suddenly, space stopped heaving around me and I was on terra

firma once more, and so, miraculously, was the horse.

I gazed hypnotically at the Tibetans as they crossed, wondering if their

calm was natural or assumed and coming to the conclusion that if it was natural

it was supernatural – and if any philosopher reading this book thinks that a

paradox – let him cross that bridge.

| "The path was moving beneath our weight and stones being

kicked off the edge would turn and jump all the way down in horribly delayed

fashion to disappear in the river far below.

There was not a tree or bush or scrub even to break that slowly executed

drop to eternity."

Click on photo to enlarge |

For

some time after that, I was unconscious of my surroundings as I pondered on the

mutability of things in general and bridges in particular and only noted vaguely

that we were climbing again. It was

the roar of the river gradually increasing which brought me from the speculative

to the real and I noticed that the river of our morning’s journey was once

again in sight and was now raging forward in snarling flood.

While the alley had widened perceptibly, the river was still confined to

the narrow limits of the gorge and was racing forward to pour itself into a

larger river flowing at right angles to it.

Just before meeting this river ahead it had to pass through a narrow

channel of solid rock, rising on both sides sheer out of the depths, and it was

the roar from its foaming madness at this immovable barrier which had attracted

my attention.

As

I said, we had been climbing steadily over the shoulder of the mountain and we

were now nearing the ridge where we would be in a position to scan the country

for miles around. Already I could

see that an impassable range of mountains lay ahead from north to south and that

we would have to turn down the valley to the south before we could find a way

through. This was confirmed, when,

topping the ridge, I saw a large unfordable river filling the valley as well.

The confluence of the two rivers blocked the way to the north so the way

to the south alone was left. If the

valley out of which we had just come was savage, the one we now entered was

majestic, although it had something of the same cruelty.

Perhaps the feeling was lessened somewhat by the greater width and calm

of the river and the greater height at which we were traveling, for we were now

five or six thousand feet above the river below.

This was the Dza Chu or Mekong River, I gathered from the map.

As we went forward parallel to the river the trail became more and more precarious, and Loshay went ahead with Dawa Dondrup while Aku followed behind me. The path, such as it was, was only about two feet wide, and wound upwards across the sheer face of the mountainside. This in itself would have been difficult enough to negotiate, but there was also a loose scree slope to be considered. While I held myself easily in the saddle with an appearance of nonchalance I could yet feel my abdominal muscles contracting into a hard lump. The path was moving beneath our weight and stones being kicked off the edge would turn and jump all the way down in horribly delayed fashion to disappear in the river far below. There was not a tree or bush or scrub even to break that slowly executed drop to eternity. I kept my eyes glued to a spot about a yard behind Loshay’s horse and eased my feet until they were almost out of the stirrups, hoping that I might be able to make a safe landing if I had to throw myself off my horse.