A Word from the Founder

|

A Word from the Founder |

|

Long Riders on the Roof of the World:

Two Centuries of Tibetan Equestrian Travel

by

At the dawning of the 21st century it is standard practice to view Tibet as the beautiful mountainous homeland of spiritual Buddhist monks. Given the peaceful teachings of His Holiness, the Dalai Lama, it is easy to understand why the Tibetans are commonly associated today with the benign influences of Buddhist philosophy, for despite the illegal occupation of their homeland by the Communist Chinese, the majority of Tibetans prefer to follow the non-violent teachings of their exiled leader rather than seek revenge against their brutal occupiers.

However, what few remember today is that in spite of its peaceful reputation Tibet has the dubious honour of being the only country The Guild is aware of where Long Riders were repeatedly murdered. As this investigation of Tibetan equestrian travel history demonstrates, some of the most astonishing and dangerous horse journeys ever undertaken came to tragic conclusions in what was once known as “the hermit kingdom.”

The subject of Tibetan equestrian exploration could be said to begin with Marco Polo, who mentioned Tibet but did not visit the country on his way to Peking. In contrast to this commercial Italian traveller, the most common European visitors to Tibet were originally Catholic priests, a number of whom travelled there from China and India starting in 1624. The Capuchins even founded a mission in Lhasa in 1729.

But by the dawning of the 19th century the foreign priests had been asked to leave and the mountainous kingdom had voluntarily isolated itself from the world at large. This policy of intended segregation soon turned Tibet into a geographical mystery, a place on the map where foreigners were neither wanted nor allowed. Yet this political seclusion backfired on the country’s leaders as it ended up inspiring curious outsiders to try and penetrate the mountainous blockade. Thus for more than a century, from the 1840s until the 1940s, one of the most elusive geographical prizes on Earth was Lhasa, the country’s restricted capital.

|

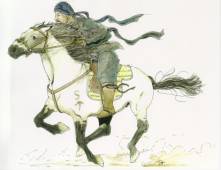

Though it is now commonly thought of as a peaceful country, in previous

centuries armoured Tibetan cavalrymen roamed the Tibetan plateau, protecting a

country the size of western Europe from foreign intrusion. (Click on this or any other picture to enlarge it.) |

Because they were intellectually curious, but unable to send official dignitaries, the British government in nearby India initially instituted a system of native spies, known as pundits, secretly to map the main roads in and out of Tibet. The pundits were amateur native spies who posed as commercial travellers, attaching themselves as nondescript pedestrians to caravans going into Tibet. While these men were undoubtedly brave, their academic discoveries were limited by the great secrecy they were forced to exercise in order not to be arrested and killed by the increasingly xenophobic Tibetan rulers.

By the late 19th century the mighty Russian empire authorized its most celebrated explorer to go into Tibet in search of knowledge regarding roads, trade and natural history. It was with the arrival of this Russian Long Rider that the modern age of equestrian exploration in Tibet began, for with the unannounced arrival of General Nikolay Przhevalsky in northern Tibet came the dawning of an age when mounted foreign explorers tried to penetrate the country, often illegally, for more than a hundred years.

The results of attempting to ride in Tibet, then and now, were always perilous, occasionally murderous, and are documented here for the first time.

General Nikolay Przhevalsky was Imperial Russia’s most famous explorer. He made four equestrian journeys in Central Asia, crossing the Gobi desert, the Tian Shan mountains and exploring northern Tibet before dying on expedition in today’s Kyrgyzstan. An avid naturalist, Przhevalsky is credited with making hundreds of discoveries including the wild Bactrian camel and the Przhevalsky horse, which is named after this famous Long Rider. The extraordinary life of this important equestrian explorer was recounted in the book, “The dream of Lhasa : the life of Nikolay Przhevalsky, explorer of Central Asia,” by Donald Rayfield. This account explains how the Tibetans, who were busy trying to thwart the British from entering their country in disguise from the south, were taken by surprise when the Russian general boldly penetrated their country instead from the north in 1880. Though he did not reach Lhasa, Przhevalsky made an extended equestrian investigation of the northern parts of the country.

|

General Przhevalsky is usually remembered today for discovering the wild Central Asian horse which now bears his name. |

Unlike his Russian rival, Captain Hamilton Bower set out in 1890 to explore Tibet in secret. His expedition, which had been authorized by the British intelligence service, was beset by many difficulties including brigands, stolen horses, and suspicious Tibetans. At one point, having had his horses stolen, Bower wrote, “I had come to the conclusion that an explorer’s life is not altogether free from anxiety.” Even though he was eventually remounted, Bower was stopped by Tibetan authorities before he could reach Lhasa. The English explorer was ordered out of the country, though he was allowed to ride towards the Chinese frontier instead of being forced to retrace his route to India. Upon his return to England, Bower was awarded the Royal Geographical Society’s Founders Medal for being the first Englishman to have crossed the Tibetan plateau. In addition to the military information he gathered, this army spy had also returned with 51 rare birch-bark leaf manuscripts acquired from a native treasure hunter. Bower’s discovery of these ancient manuscripts prompted a scramble for artefacts by Europeans and led to further intrusions into Tibet. The story of Bower’s trip, “Journey Across Tibet,” will soon be republished by The Long Riders’ Guild Press.

One fact that has always struck us here at Long Riders’ HQ is how utterly different equestrian explorers are, one from the other. And yet despite their differences, they all share two common threads. They all speak “horse” and they have a need to explore the world on horseback, no matter what the cost.

As is if to prove the authenticity of this finding, and in complete opposition to the bold military men who had proceeded her, came a most unusual equestrian explorer, for of all the Long Riders who ever ventured into Tibet, none was so unprepared by her original lot in life than Isabella Bird.

No one could have foreseen the amazing life that lay ahead for this clergyman’s daughter. Of moderate means, blessed with ill-health, unwed, physically unimpressive, Isabella Bird had every reason to stay at home in the safety of her English village. She chose instead to venture out into the world, a place in the late nineteenth century still full of dangers, brigands, discomforts, and unexplored countries.

And, whenever possible, Isabella chose to see the world from the back of a horse. Bird’s journey among the Tibetans is one of her five famous equestrian trips. She had made the first documented equestrian exploration of the Hawaiian Islands, crossed the Rocky Mountains on horseback, likewise explored Japan with her saddle and went on to canter across Morocco when she was in her seventies. But of all her equestrian adventures, her ride through Tibet takes precedence. For it was here, in this vast, windswept, frozen northland that the intrepid English woman nearly met her match!

She and her little horse, Gyalo, were dashed into icy rivers. They crossed passes so high that the porters begged for mercy. They saw more adventure, and covered more miles than had ever been experienced by a female equestrian explorer, and her account of riding Among the Tibetans in 1894 provided the outside world with one of it’s first peeks at the mountain kingdom.

| Despite its legendary hostility, tiny Isabella Bird, and her equally diminutive mount, Gyalo, weren’t intimidated by Tibet. |

The nineteenth century can rightly claim to have seen the birth and travels of a host of brave men and women who undertook great hardships in their quest for adventure. Legendary names come to mind like Sir Richard Burton and Sir Ernest Shackleton. Yet sadly, one name is largely forgotten today, that is Henry Savage Landor.

Though Savage Landor became justly famous for making a series of trips to many outlandish and dangerous places, none of his trips aroused public sentiment like his famed journey through Tibet in 1898.

Fearing her covetous foreign neighbours in British-occupied India and Imperial China, the high Himalayan country had sealed her borders to outsiders. Thereafter a number of Europeans, including Bower, had been detected by Tibetan officials and turned back before they could reach the nation’s isolated capital at Lhasa.

With such a geographic prize at stake, Savage Landor determined to set off with a small group of native porters to reach the Tibetan capital by stealth. To say he failed would be too polite a term for what occurred next. After making his way across vast and primitive lands, the would-be equestrian explorer was detected by the Tibetans and arrested. Once they determined that the Englishman was travelling without the official sponsorship of his government, the situation turned from bad to worse.

Savage Landor and his servants were first imprisoned, then brutally tortured. At one point the explorer had his arms tied behind his back. He was then mounted on a half-wild horse, placed in an infamous “torture saddle” that had spikes sticking into his back, and forced to ride many miles, all the while being slowly torn to bits by the cruel spikes. Illustrated with hundreds of photographs and drawings, the author’s blood-chilling account of equestrian adventure, In the Forbidden Land still makes for page-turning excitement.

| After being captured by Tibetans, English Long Rider Henry Savage Landor was tortured by being forced to ride across Tibet in a spiked saddle. |

Though Sweden has had many brave sons set out to explore the world, few were as remarkable as Sven Hedin, who spent almost twenty years of his life on Asian soil.

Originally, he aspired to follow the path of other late nineteenth century Swedish explorers and engage in polar research. But an offer to serve as private teacher to the son of a man who worked in the naphtha fields of the Nobel family in Baku directed his attention to Asia. After completing his work Hedin embarked on a ride through Persia, which taught him how to endure both physical and economic hardship en route. Hedin’s Persian exploits drew him further into Asia, acquainting him with its people and history.

At the beginning of one journey that lasted three years, Hedin wrote, "The whole of Asia was open before me. I felt that I had been called to make discoveries without limits - they just waited for me in the middle of the deserts and mountain peaks. During those three years, that my journey took, my first guiding principle was to explore only such regions, where nobody else had been earlier."

During his adventurous lifetime

Hedin discovered lost cities in the Gobi desert, criss-crossed Central Asia four

times, mapped previously unexplored mountain ranges and came within a few miles

of reaching Lhasa disguised as a lowly porter in 1900. His autobiography, My Life as an Explorer

recounts his Tibetan equestrian adventures and regales the reader with almost

more adventure than one can bear to read.

|

Swedish Long Rider Sven Hedin endured a great many hardships while riding across Tibet but was eventually turned back from Lhasa by suspicious officials. |

Tibet's self-imposed isolation was

interrupted at the beginning of the twentieth century when a Buddhist monk named

Dorjieff succeeded in winning the favour of the country's spiritual ruler, the

Dalai Lama. To complicate matters further, the clever Dorjieff had also enlisted

the interest of Czar Nicholas II of Russia. When the Buddhist monk convinced

the Russian Czar to invite the Tibetan ruler to Moscow, the international stage

was set for political disaster.

Despite the objections of his own xenophobic governmental advisors, the Dalai Lama accepted the Tsar's invitation. Yet this journey was never meant to be. When the news reached Delhi that Russia was interfering in Tibetan internal affairs a political panic spread across the British Indian empire. Lord Curzon, the viceroy of British India, an arch-Russophobe, and a Long Rider who had explored the Pamir Mountains on horseback, perceived the Russian move as a threat to England’s Indian Empire. Curzon immediately ordered Colonel Francis Younghusband to invade Tibet.

In 1904 after several bloody and unequal battles against Tibetans armed with medieval weapons, the British army forced its way into Lhasa only to find that the thirteenth Dalai Lama had fled to Mongolia, a Buddhist land that had been an early protector of Tibet. The British victors were left holding an empty throne.

But their forceful intrusion into the neutral sovereign nation of Tibet had far-reaching implications not only for the country, but for Long Riders in the 20th century.

Within a decade of the invasion the wheel of history had turned. The British Viceroy signed an agreement with the Russian Czar ending their competition in this final chapter of the Great Game. By 1913, though the British were the pre-eminent foreign power in Lhasa, the Tibetans attempted to resume their national policy of spiritual and political isolation.

But events on the world stage were conspiring against a resumption of hermit style policies. As the twentieth century advanced, an increasingly militant Japanese empire began to threaten the British empire from an unexpected direction. So while the Tibetans quietly managed their own affairs for the next thirty-seven years, the world inexorably marched towards the on-coming disaster of the Second World War.

| The Potala is the legendary home of Tibet’s hereditary ruler, the Dalai Lama. Tibetans believe the successive Dalai Lamas form a lineage of reborn rulers which traces back to 1391. According to Tibetan Buddhism belief the Dalai Lama is the incarnation of Avalokietsvara, the saint of compassion. A succession of Dalai Lamas ruled Tibet between the 17th century until the 1950s, when the current Dalai Lama fled the Chinese Communist rule of his country. |

But before the world embraced the madness of the world war, Tibet granted herself a special equestrian reprieve. This occurred in the early part of 1940 when a new Dalai Lama was chosen to rule the country. The fourteenth spiritual ruler of the country, whose journey into exile continues to interest the outside world, assumed the throne at the young age of seven.

In 1940 the tiny ruler’s older brother, Thubten Jigme Norbu, rode across Tibet to visit his newly enthroned sibling. That “Story from the Road” entitled A Caravan Journey from Kumbum to Lhasa recounts how this Tibetan Long Rider witnessed an unspoiled and slumbering country, a Tibet still quietly humming its ancient prayers and unaware that the cataclysmic world war was about to come riding into its capital.

Years later when he recalled his equestrian journey to Lhasa, Norbu recounted how his modest caravan of twenty-two men set off with no less than a hundred and twenty animals for the journey. Yet by the time Norbu had crossed Tibet his caravan had joined forces with an assortment of other mounted travellers. The resulting massive migration was estimated to contain a thousand travellers and twenty-thousand animals.

Yet this was the calm before the storm and the world which Norbu witnessed was about to become a beloved memory.

| Tibetan Long Rider Thubten Jigme Norbu (left) is seen with his younger brother, Tenzin Gyatso, His Highness the Dalai Lama. The two brothers represent the religious, cultural and equestrian traditions now threatened by the repressive Communist Chinese occupation of Tibet. |

Though Henry Savage Landor had been treated harshly when he was caught trespassing in Tibet, the foreign Long Riders who attempted to break the Tibetan political blockade had generally been treated with courteous fairness.

All that changed when blood-thirsty brigands not only murdered a Long Rider, but also slew the late 19th century game of “tag” which Tibet had been previously willing to play with uninvited intruders.

The rules which said that Lhasa would simply send an explorer back home were forever altered when two idealistic young Frenchmen rode into the forbidden kingdom and encountered equestrian disaster.

Born in the same year of 1904, Andre Guibaut and Louis Liotard became acquainted in the merchant marine. Determined to become famous explorers, the two studied geography courses in Paris, then set off for Tibet. Because their first venture into the country had gone undetected the French Long Riders felt emboldened with success.

So they set off in the spring of 1940, determined to enter into Tibet via China’s Yellow River gorge. This border area was notoriously dangerous, and years later, Guibault recalled visiting one crime ridden town. “Robbers abound in this frontier post and it is common at dawn to find people lying stabbed and entirely stripped of their clothes.”

Alas that the brave young Frenchmen did not pay more heed to the dead bodies which served as a warning for what was to come, for on September 10th they were ambushed. A hail of bullets fired by concealed brigands slew Louis Liotard in the saddle. Andre Guibaut was forced to retreat or die. Liotard, whose body was never recovered, was awarded the Legion of Honour posthumously.

Then, with the world rapidly descending into the madness of the Second World War, Andre Guibaut was appointed to the French diplomatic service by General De Gaulle.

Yet this bloody prequel had set the stage for the appearance of two unusual Long Riders riding into Tibet.

| French Long Rider Louis Liotard was thirty-six-years old when he was murdered by Tibetan brigands in 1940. His death was recounted in Andre Guibaut’s 1947 book, “Tibetan Venture.” |

Soon after the Frenchman died a remarkable thing occurred. The American president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, decided to send a mounted delegation to Lhasa. Like all political events, there were public and private reasons behind this decision.

By the spring of 1942 the war against Japan and the Nazis looked grim. The Japanese had conquered the eastern portion of the previously impregnable British empire, starting with their capture of the fortress of Singapore and concluding with their occupation of Burma. With India threatened, and their allies in China surrounded by hostile Japanese forces, Roosevelt and Churchill hatched the idea of using the mountainous kingdom of Tibet as a transit station for supplies to be moved overland from India to China.

Mind you, there were a few small problems with this plan.

In addition to climbing over the natural obstacle of the mighty Himalayan mountains, there was the danger of dying of altitude sickness brought on by trying to make your way across the highest country in the world, not to mention the legendary antagonism expressed by most Tibetans towards unwelcome outsiders.

But what the Tibetans didn’t know was that FDR was a fan of their country. Having read the romantic novel “Shangri-la,” the president became intrigued with the mysterious mountain kingdom. He even dubbed the presidential retreat Shangri-la, though more pragmatic presidents now call it Camp David. So when the idea was presented to him for an official American diplomatic mission to ride from India, over the mountains to Lhasa, and then make their way overland through the backdoor of China, Roosevelt couldn’t say “no.”

Enter the most unlikely Long Rider in Tibet’s long history, the dashing Count Ilya Tolstoy.

Roosevelt’s appointed Long Rider ambassador was a grandson of the famous Russian author, Leo Tolstoy. The elder Tolstoy was so passionate about horses that his friend and fellow author, Ivan Turgenev, accused him of having been a horse in his previous life! The famous author of War and Peace, who had hosted the Swedish equestrian explorer Vladimir Langlet, rode right up to his death. Coming from such a strong equestrian background, it was no wonder the author’s grandson, who had studied and settled in America before the war, was chosen by Roosevelt to head this delicate equestrian diplomatic mission.

Accompanying Tolstoy was Captain Brooke Dolan, a brilliant Princeton University naturalist turned US army spy.

Their mission was simple.

Go to India. Find horses. Ride over the Himalayas to Lhasa without getting killed. Introduce themselves to the Dalai Lama. Entice him to become a diplomatic ally. Then ride on to China before reporting back Washington DC.

Easy !

To assist them FDR provided the Long Rider ambassadors with a number of lovely gifts deemed appropriate for the young ruler of Tibet, including a silver framed photograph of the president and a precious gold chronograph watch.

By September, 1942 both men had reached northern India, been outfitted with horses and a number of mounted guards, then told, “Keep in touch if you can.”

| With the silver framed photograph of President Roosevelt went a personal letter to the Dalai Lama in a cylindrical casket, a gold watch and other gifts. The silver galleon (right centre) was presented to His Holiness by Colonel Tolstoy and Captain Dolan. |

After riding over 14,000 foot high passes, floating their horses across the Brahmaputra river on an ancient flat-bottomed barge, and convincing a number of suspicious Tibetan officials that they were ambassadors, Tolstoy and Dolan reached the small town of Yatung. There they were honoured by receiving from Lhasa the Red Arrow Letter, a courtesy gesture from the Dalai Lama’s court which authorized them to travel through the country. Armed with this ancient symbol, and four months after they entered the sparsely inhabited country, the weary Long Riders reached Lhasa and were finally introduced to the boy ruler of Tibet.

Because of their special status, the Long Riders had even been allowed a special privilege.

Because of their special status, the Long Riders had even been allowed a special privilege.

“Usually visitors must make a long and tedious climb up the broad steps of the Potala palace,” Tolstoy recalled. “We, however, were extended a great courtesy, being allowed to ride along a narrow path up the mountain to the back of the palace, where we left our horses. Then we were escorted through the courtyards and long labyrinths of the Potala.”

| Count Ilya Tolstoy, left, Captain Brooke Dolan, centre, and a mounted Ghurkha guide can be seen riding across Tibet in 1942. |

(The Guild would like to thank Professor Robert Linrothe for preserving the precious Tolstoy-Dolan photographic collection. For more information, please visit Professor Linrothe’s on-line gallery.)

What Tolstoy and Dolan discovered was an intelligent ten-year-old lad who was keenly interested in the outside world. While the young Dalai Lama was eager to interact with the diplomats, his guardians were less encouraging. While cautiously welcoming of western assistance, the Tibetans feared an open alignment with America and England might anger their Chinese neighbours, who, even though they were involved in a battle to the death with the Japanese, still cast covetous eyes on Tibet.

And there was another reason to be cautious. According to Tolstoy’s report to his superiors in the American Office of Strategic Services, the precursor of the CIA, “the present Tibetan government regards motor vehicles as modern and anti-Tibetan.”

With their mission essentially concluded, and no formal permission for a road having been granted, the Long Riders received permission to depart in February, 1943. Their equestrian journey didn’t end however until they rode into a Chinese frontier outpost on June 21st.

After their return to the United States, Dolan was sent back to China. Sadly, the young naturalist, turned army officer, was killed soon after combat had been officially concluded with Japan. So it was left to Tolstoy to record the tale of their remarkable equestrian journey in his “Story from the Road,” entitled Across Tibet from India to China.

For the next few years no strangers came riding into Tibet. Much of the world was in ruins after the war and next door in China, Chang Kai-shek’s nationalist troops were busy battling Mao Zedong’s communists for ultimate control of the country. But by the spring of 1949, with the communists on the verge of seizing complete control of China, three remarkable Long Riders, a notorious adventurer, a man of God, and a spy on the run, came galloping into Tibetan equestrian history.

A One-Man Campaign

Leonard Clark was a lifelong enemy of fear, common sense, and all the other elements that usually define “normal” people. Though only twenty-six when he first ventured into Asia in the early 1930s, he soon developed a style which saw him always armed with a keen eye, a sense of humour, no regrets and his trusty Colt 45 pistol.

Before the onset of the war, Clark had delighted in telling his readers how he outsmarted warlords, avoided executioners, gambled with renegades and hung out with an up and coming Communist leader named Mao Zedong. In a world with lax passport control, no airlines, and few rules, the young man from San Francisco floated effortlessly from one adventure to the next. When he wasn’t drinking whiskey at the Raffles Hotel or listening to the “St. Louis Blues” on the phonograph in the jungle, he was searching for Malaysian treasure, being captured by Toradja head-hunters, interrogated by Japanese intelligence officers or lured into shady deals by European gun-runners.

| Before becoming a Long Rider, Leonard Clark had been a dare-devil aviator and espionage agent. So it wasn’t out of character for him to announce the he was going to raid Tibet on horseback. |

With such sterling references it wasn’t surprising that during the Second World War Clark was chosen to head the United States espionage system in China. When that global conflict was concluded, Clark turned his relentless energy towards exploring the most dangerous and inaccessible places on the globe. Case in point was his decision to lead a mounted expedition of Torgut tribesmen into Tibet.

The official reason for Clark’s decision to venture into the mountainous kingdom

on horseback in early 1949 was to find and measure a mysterious mountain in the

Amne Machin range rumoured to be higher than Mount Everest. The only problem was

that the sacred mountain was guarded by the fearsome Ngolok tribesmen. Yet

romantic adventure ran deep in Clark, which helps to explain why he was

journeying through one of the world's least known and most forbidding regions in

the centre of Asia.

There were also been rumours that Clark would use his equestrian expedition to launch an anti-Communist rebellion in Central Asia and prepare an impregnable base for General Ma Pa-fang, a violently anti-communist Moslem general.

In his book

The Marching

Wind Clark

describes the panoramic story of his mounted exploration in the remote and

savage heart of Asia, a place where adventure, danger, and intrigue were the

daily backdrop to wild tribesman and equestrian exploits. Amply illustrated with

Clark’s photographs, as well as maps he drew in Tibet, this rediscovered classic

was originally published shortly before the intrepid author died in a Venezuelan

jungle looking for diamonds.

Tibet has never been short of miracles, so it shouldn’t surprise you to learn that when the Chinese Communists decided to invade the ancient kingdom of Tibet it was a Long Rider who galloped over the Himalayas in search of help.

Soon after the Second World War concluded a young Scottish medical missionary named George Patterson followed a special calling to travel to Tibet and be of spiritual and medical use to the country’s people.

Patterson, who eventually spoke the language fluently, became Tibetan in all but name by adapting the country’s clothing and customs. The talented horseman was thereafter befriended by the leaders of the powerful Khamba tribe of Tibetan horsemen. So it was thanks to his companionship with God and his own strength of character that Patterson found himself immersed in a lifestyle so full of adventure that in today’s tame world it seems nearly unbelievable.

It was this unique combination of skills and coincidence which caused George Patterson to undertake an emergency equestrian journey across the wildest parts of Tibet.

In 1950 the Chinese Communists sent an ultimatum to the leader of the Khamba horsemen. Determined to “liberate” Lhasa and seize the entire country, Mao Zedong’s triumphant communists gave the Tibetans two options, surrender or be destroyed. Patterson’s host and friend, the Tibetan leader known as Topgyay Pangdatshang, realized his poorly armed countrymen could never resist the advancing Red army. If any help was to be found, a warning had to be taken through to India. The only way to achieve this was by riding over the Himalayas. The problem was that the Tibetan leaders feared that western leaders in Delhi, India would be sceptical of an unsubstantiated plea for help from a native Tibetan. That’s when they turned to “Patterson of Tibet.”

Though it was winter George was asked to ride over the Himalayas, down into northern Assam, then venture on by rail to Delhi in the hope of organizing a diplomatic and military rescue. But before Patterson ever worried about reaching the warm capital of India, the Long Rider had to consider the minor fact that he was being asked to ride over 20,000 foot high mountains in sub-zero temperatures. Plus there was the minor inconvenience that even the Tibetans weren’t sure if the proposed route was passable.

| Long Rider George Patterson, (left) and his Tibetan companion, Loshay, made a historic journey over the Himalayas in the vain hope that the United States, England and India would come to the rescue of Tibet. |

Yet Patterson’s faith in God, and his desire to help Tibet, weren’t going to be denied. The snows on the high passes might beat him, but if he could find the villages he had authority to commandeer relays of food and transport. As for his companions, the Khamba tribesmen who rode with him were Tibet’s most noted horsemen. Besides, after having lived through the harsh Tibetan winters, the Long Rider was a superb horseman whose body was as efficient as the Tibetans’ in low temperatures. The resultant ride saw Patterson, and his main companion, the Tibetan named Loshay, risking their lives countless times as they rode south through the snow-covered mountains with their desperate message.

Tragedy was Patterson’s reward.

Though Tolstoy and Dolan had come bearing gifts, in Tibet’s hour of need the United States and Great Britain forgot their previous promises. They watched instead from the sidelines as the Chinese first invaded, then put the country to the sword. There was some diplomatic lip-service from London and Washington but their words were hollow. Tibet was imprisoned in Chinese chains and Long Rider George Patterson was the last outsider to ride across a free Tibet. This remarkable Long Rider, who is now in his mid-80s, recounted his astonishing journey in his amazing book entitled, Journey with Loshay.

How ironic then that the next Long Rider to venture into Tibet was an American spy fleeing from the same Red Chinese whom Leonard Clark and George Patterson tried to halt.

Murder in the Atomic Age

They called it the Atomic Age because Hiroshima and Nagasaki had been levelled by atom bombs. Yet even though the threat of mass mayhem had been let loose on the planet, over in occupied Tibet the ancient concept of personalized murder still lurked on the trail leading to Lhasa.

With George Patterson busy in Delhi trying to convince Indian Prime Minister Nehru to assist Tibet, and Leonard Clark galloping around with Torgut tribesmen looking for a mysterious mountain, a Long Rider tragedy was about to unfold in Tibet.

In the immediate post-World War II period the Soviet Union began work on its own atomic program. In order to monitor their progress the newly created CIA sent their agent, Douglas MacKiernan, to Urumchi, a city in China’s western Sinkiang Province. Working from that consulate MacKiernan investigated the Soviet mining of uranium in northern China and secretly planted electronic sensors to detect the Soviets' first atomic blast on August 29, 1949, in Kazakhstan.

When the Communists seized control of China MacKiernan was ordered to evacuate. But conditions in the east had deteriorated so seriously that MacKiernan had only one option, escape by horseback across one of the worst deserts in the world and ride on to the still free Tibetan capital of Lhasa. Accompanying him on this wild mission would be Frank Bessac, an young American student turned espionage agent who had been patrolling the Chinese-Mongolian border, and three fervent Russian anti-communists.

Before this unlikely group saddled up MacKiernan wired Washington DC to report that the communists were expected to seize Urumchi immediately. Then, with his official duty done, MacKiernan, Bessac and the Russians set off towards Tibet with their gear, which included machine guns, radios, gold bullion, navigation equipment, and survival supplies.

Ahead of them lay the notorious Takla Makan desert, which they managed to cross after great hardships. The spies turned Long Riders were then forced to ride up into the mighty Himalayas in order to reach Tibet. During the course of their journey MacKiernan had managed to radio Washington to report their progress. The American government in turn had managed to send word to the Dalai Lama’s government, asking the Tibetans to extend diplomatic sanctuary to MacKiernan and his men when they reached Lhasa.

The problem was that MacKiernan and his men were due to enter Tibet before any official word of greeting could be sent from Lhasa to the border. And unlike Tolstoy and Dolan, who had been carrying the Dalai Lama’s easily recognizable two-foot-long “Red Arrow” of introduction, MacKiernan’s group had no such visible sign of authority.

Under such rare conditions are disasters born.

After having struggled over the Himalayas, MacKiernan, Bessac and the Russians believed their freedom was in sight.

Before them lay the Tibetan outpost which spelt safety.

It was April 29th, 1950, Douglas MacKiernan’s birthday – and he was about to die.

According to recently released, previously top-secret American State Department documents obtained by The Long Riders’ Guild, MacKiernan and his men were attacked by the Tibetan border guards. MacKiernan and two of the Russians were slain. Bessac and the remaining Russian were wounded. The Tibetans then tied up the two survivors, threw them on their horses and began heading them towards the still distant Lhasa.

Marching before the dazed Bessac was a baggage camel carrying a filthy sack. With his own life hanging by a thread the wounded American didn’t comment on what he knew was swinging back and forth before him, for his Long Rider comrade, MacKiernan, had been beheaded on his birthday. And that grisly trophy, along with the heads of the deceased Russians, now led the way to Lhasa.

| CIA agent, turned Long Rider, Douglas MacKiernan lost his life trying to ride across Tibet in 1950. |

With Bessac captive and radio contact broken off, rumours began swirling across Central Asia that MacKiernan may have been wounded or slain, so Washington directed its agents to ask George Patterson for help. Upon reaching India the Long Rider had instantly delivered his appeal for help, only to see it rejected by the various world powers. Soon afterwards Patterson fell ill. It was while he was recovering, and planning on returning to Tibet, alone if need be, that agents of the American government attempted to enlist his aid in finding the missing MacKiernan.

Knowing of George’s medical background, his intimate knowledge of the country and his ability to speak Tibetan fluently, the American State Department believed the Scottish Long Rider might be able to locate MacKiernan and guide the missing agent and his men to safety.

Yet before Patterson could set off, word reached Washington that though Bessac had reached Lhasa alive, his CIA boss was slain. The Dalai Lama’s government expressed official sorrow at the murderous border mix-up. But they had other things on their mind. With MacKiernan dead, Bessac on his way to India, Patterson ill, and Clark gone, Tibet was left to face the invading Chinese. Eventually the Dalai Lama fled the grasp of his captors. But before he left Lhasa he took along the “magnificent” gold watch presented to him by President Roosevelt’s Long Rider ambassadors.

In an ironic Tibetan twist of fate, even though Douglas MacKiernan was the first CIA agent killed in the line of duty, his work remains so sensitive that the Agency still refuses to either confirm or deny his existence. To learn more about the death of this James Bond style Long Rider, The Guild recommends, “Into Tibet: The CIA’s First Atomic Spy and His Secret Expedition to Lhasa,” by Thomas Laird.

Upon returning to the United States his astonishing story was written up and published in Life magazine under the title, “This Was the Perilous Trek to Tragedy,” 13th November, 1950. He later became Emeritus Professor of Anthropology at the University of Montana. After waiting fifty years for previously secret documents to be de-classified, Frank has just published his incredible story in a new book entitled, “Death on the Chang Tang.” For details on how to purchase this important work, please contact The Guild.

The details of Bessac’s amazing journey across Tibet, as well as the details of MacKiernan’s death, were recorded in an amazing diary which the American Long Rider kept during this unique adventure. This singular document was recently discovered by a scholar and friend of Long Rider George Patterson. Entitled Bessac’s Journey, this declassified document makes for hair-raising reading and is made available to the public for the first time here as a Guild “Story from the Road.”

The Curtain Drops

There was one final small Long Rider act yet to play before the Iron Curtain fell across Tibet.

Though he had fought unsuccessfully for years on a number of diplomatic fronts, George Patterson had been forced by international events not to return to Tibet. So by the early 1960s George had hung up his saddle.

But what do you do when adventure calls at an inopportune time? Who do you turn to, but God, when you need answers to how you should travel along an uncertain road? These were the type of personal and spiritual dilemmas George Patterson faced when risk knocked at his door late one night. The missionary turned Long Rider had married brilliant Scottish scientist, Dr. Meg, and they were raising a family, when his adopted homeland entered their life one last time.

Think of Tibet, that frozen kingdom hiding behind its protective barrier of high mountains. Now add in the fact the Red Chinese had recently placed a bounty on Patterson’s head for his role in helping orchestrate the escape of the Dalai Lama. Next, bring in a band of determined Tibetan guerrillas who offer Patterson a chance to witness their attack on the invading Communist army. There’s just one catch – he has to leave his wife and children long enough to accompany them on what looks like a one-way journey. The problem is no other westerner can get into Tibet, except Patterson, so the outside world is oblivious to the Chinese atrocities being perpetrated on the Tibetans. That’s why the rebels need Patterson of Tibet to make one last journey. Just before you leave on this literary journey of a lifetime, don’t forget to tie down the independent English film-maker who will document this amazing journey with the Tibetan rebels.

Now you’re ready to set off on a roller-coaster of a ride packed with undercover action, fast-shooting freedom fighters, revengeful Communists and a Scotsman who’s seen more excitement than a dozen other men. The resultant book, Gods and Guerrillas is a rare glimpse into the 1960s forgotten war when a handful of Tibetans took on the might of the Red Army.

| Scottish Long Rider George Patterson, (right), has spent his life helping Tibet and its spiritual ruler, His Highness the Dalai Lama, (centre). |

But after George returned from this guerrilla raid into Tibet, there would be only equestrian silence for more than fifty years, until the unlikely appearance of two Long Riders from opposite ends of the earth, who happened to share the same last name and the same desire to revive the time-honoured tradition of equestrian exploration in Tibet.

If the communist rulers of occupied Tibet had bothered to ask The Long Riders’ Guild what would eventually occur, we would have told them that despite their restrictions, sooner or later a new generation of adventurous humans would mount up and once again set off across the roof of the world.

And even though Beijing neglected to consult us, that’s exactly what happened.

For nearly fifty years China has imposed her own brand of crushing colonialism on Tibet. It has murdered Tibet’s people, slain her ancient customs, uprooted her religion, forced her ruler into exile and driven a high-speed rail line into her countryside like an iron stake. Yet despite these horrors the allure of ancient Tibet still shines through the political corruption.

And that is what inspired Ian and Daniel Robinson to travel from opposite ends of the globe so as to explore Tibet on horseback.

New Zealand Long Rider Ian Robins was the first to go.

He had already explored Mongolia alone on horseback. So after the death of his Tibetan spiritual advisor in New Zealand, Ian vowed to deliver his teacher’s ashes to Mount Kailas, Tibet’s most sacred mountain. The resultant epic attempt to cross Tibet on horseback began in 2002. That’s when Ian set out to ride from the eastern border of China, straight across the heart of Tibet. Along the way the intrepid equestrian explorer fought off bitter cold and altitude sickness – all to no avail. When word reached the Chinese authorities that a lone foreigner was attempting to ride across portions of Tibet which they had declared “off-limits,” they sent a police posse out to find him.

Ian was arrested and placed under house arrest in a tiny hotel. Though his horses had been confiscated, he decided not to give up. He bluffed his way past the guards, made his way into town, purchased two more horses, and with police jeeps in pursuit, rode for the hills. He eluded the authorities across half of Tibet and nearly made it to the sacred mountain.

Eventually the Chinese authorities cornered him. This time they were taking no chances, so they deported him straight back to New Zealand.

But like a character from the movie, “The Great Escape,” the New Zealand Long Rider refused to give up.

He returned to Tibet, bought another horse, and this time by managing to evade contact with the authorities, the determined equestrian explorer reached the sacred mountain on the far side of Tibet.

Ian’s remarkable story of riding across the width of Tibet is recounted in his thrilling book, “You Must Die Once.” And he has kindly shared one of his adventures with The Guild’s readers in this “Story from the Road,” entitled Riding to Mount Kailas.

| Upon reaching Mount Kailas, the sacred mountain of Tibet, Long Rider Ian Robinson gave his horse, Monlam, to this Tibetan monk named Tashi Puntsog. |

But not all adventures end up on such a jolly note.

As history demonstrates, if you attempt to ride across Tibet you could be strapped to a spiked saddle like Henry Savage Landor, murdered like Douglas MacKiernan, or become the first equestrian traveller in the 21st century to end up in prison, like Daniel Robinson.

If Daniel had approached The Guild prior to his departure we would have warned him that the sun and moon may change but the harsh Tibetan landscape is still a man-breaker. But the former chef turned spiritual pilgrim didn’t seek any advice before trying to make his way along the Tea Horse Trail, a bone-breaking track stretching thousands of miles from western China, up and over Tibet and down into the distant plains of India. Instead he joined up with a company of Chinese traders and set off in search of that oft-times deadly combination, external adventure and internal harmony.

| In 1930 the elusive amateur biologist, Joseph Rock, made an historic mounted exploration of the mountainous regions running between China and Tibet. Because he travelled with a large mounted guard, Rock was able to have his mules and horses winched across the raging rivers of Tibet, something Daniel Robinson had to manage alone. |

“At one point I nearly died

crossing a river. The current was taking my legs away. It was freezing cold.

When you reach a point close to death it’s like turning towards the light again

and it brings you alive and makes you realise that everything in life has a

great value,” he said.

But despite the discovery of these important personal revelations, Daniel learned that there was always one more obstacle lurking just ahead on the Tea Horse Trail. After climbing a nearly 20,000 foot high mountain, for example, the equestrian explorer experienced the agony of altitude sickness. At the end of October, 2006, with the temperatures dropping, Robinson decided to head south towards Nepal and the end of his long pilgrimage along the Tea Horse Trail. The problem was that he no longer had a map, didn’t know exactly where Nepal began and had no entry visa for India. But with winter’s icy winds rushing down on him from the high slopes of the Himalayas, Robinson began trying to guide his still trusting, but now ill, mules south as quickly as possible. Then their food ran out in a vast and empty landscape. To make matters worse, the weather was trying to kill them and they were all three weary unto death.

With his animals clinging to life, and the temperature plummeting, circumstances forced Robinson to change course away from the more distant Nepal and descend instead down a mountain pass into Uttaranchal, one of India’s northern Himalayan states bordering Tibet. Thus in freezing weather and desperate for assistance, Robinson crossed the northern Indian border near Mana and entered a military zone without a visa. Yet instead of attempting to evade the authorities, Robinson sought help by walking into the Lapkhal military post near Chamoli, thereby making the fateful decision to place the veterinary requirements of his horses before his own legal needs.

Daniel was jailed by the Indian authorities, who were prepared to imprison him for ten years. Thanks in part to an international equestrian campaign led by The Long Riders’ Guild and the British Horse Society, Daniel was freed in May, 2007. Details of Daniel’s journey across Tibet, and the subsequent campaign to free him from an Indian prison, may be read in the Long Rider editorial, The Price of a Pilgrimage.

| Despite its uncertain political future and the inherent dangers of travelling there, the lure of ancient Tibet still draws equestrian pilgrims like Daniel Robinson. |

A recent news article reported that despite the fact that millions of ethnic Chinese have immigrated into Tibet, the Khampa horsemen who once hosted Long Rider George Patterson still hold their annual horse fair. Every August these wild horsemen come together on a 14,000 foot high plateau to share their stories, gallop their horses, and keep the equestrian traditions of their Tibetan past alive.

| It was Khampa horsemen, such as this, who hosted Long Rider George Patterson and resisted the invasion of their country. |

Despite the political challenges which lie ahead for Tibet, The Guild believes Ian and Daniel Robinson demonstrate that in spite of political restrictions more and more Long Riders will begin to explore Tibet on horseback. Upon their return this new generation of equestrian journeyers will have their own stories to share.

And as His Holiness the Dalai Lama is fond of saying, “Sharing your knowledge is a way to achieve immortality.”

For additional information regarding Tibet’s equestrian past, The Guild recommends “Warriors of the Himalayas – Rediscovering the Arms and Armour of Tibet” by Donald LaRocca, “Vanished Kingdoms – A Woman Explorer in Tibet” by Mabel Cabot, "Into Tibet: The CIA's first atomic spy and his secret expedition to Lhasa" by Thomas Laird, and "A Portrait of Lost Tibet" by Rosemary Jones Tung.

To learn more about Tibet's political struggle, please visit the website of the International Campaign for Tibet and listen to the monthly English-language radio magazine, "The Tibet Connection."

Finally, The Long Riders' Guild is happy to report that the equestrian exploration legacy of Count Ilya Tolstoy is being continued by Countess Alexandra Tolstoy, a Member of The Guild and a Fellow of The Royal Geographical Society. To discover how Alexandra rode the length of the Silk Road and recently journeyed on horseback from Turkmenistan to Moscow, please visit her website.

|

Visit the world's largest collection of Equestrian Travel Books! |

Back to Word from the Founder main page