Heroes of the Pampas

by

|

|

Heroes of the Pampas

by

|

When John Labouchere rode 5,000 miles through the Andes mountains, he cited one man as his inspiration. When Tim Severin rode from Paris to Jerusalem on a two-year trip, he credited the same equestrian explorer as his hero. When I rode more than 1,000 continuous miles through the Karakoram mountains of Pakistan, I offered him my silent thanks. Margaret Leigh rode the length of England and fondly remembered this man as her guiding light. Robin Hanbury-Tenison rode along the Great Wall of China. And Louis Bruhnke rode from Patagonia to Alaska.

All

because of one man – Aimé Tschiffely – the world’s

most improbable equestrian hero!

|

Aimé Tschiffely, the most famous Long Rider of

the 20th Century, and his two stalwart companions, Mancha and Gato, faced

every kind of peril - including sandstorms in the Bolivian desert.

Click on photo to enlarge

|

Seventy

years ago a quiet unassuming Swiss man with no previous equestrian experience

set the high water mark against which all 20th century equestrian

explorations are still compared.

And

he did it on descendants of the horses of the Conquistadors.

The

story of Tschiffely, Mancha and Gato, the heroes of the pampas, is the unlikely

tale of a man and two horses who the world mocked.

Decried as a suicidal Don Quixote with two old horses, their Cinderella

story has passed down into modern legend as the most important equestrian travel

tale of the 20th century.

Yet

it was a legend that almost never came to be.

Perhaps

it was in fact because he had no prior equestrian knowledge to fall back on that

29-year-old Tschiffely ignored the legion of critics who told him his quest to

ride 10,000 miles from Buenos Aires, Argentina, to Washington D.C. in 1925 was

“impossible” and “absurd.”

Not

only did this brash neophyte propose to attempt this equestrian suttee, he said

he was going to do it on two elderly horses, ages 15 and 16, owned by a

Patagonian Indian, who were currently unbroken and running free on the Argentine

pampas. In his own words, “they

were the wildest of the wild.”

It

was no wonder he had more sceptics than supporters.

Tschiffely,

who had only recently learned to ride, may not have known the difference between

a hackamore and a halter ……. but he did know his history.

Decades

before the world rediscovered the legitimate importance of the Spanish horse –

Tschiffely, an amateur historian, set out to prove that one breed, the Criollo,

was the hardiest horse alive.

He

wrote, “The Criollos are the descendants of a few horses brought to Argentina

in 1535 by Don Pedro Mendoza, the founder of the city of Buenos Aires.

These animals were the finest Spanish stock, at that time the best in

Europe, with an admixture of Arab and Barb blood.

That they were the finest horses in America is borne out by history and

tradition.”

Later,

when Buenos Aires was sacked by Indians and its inhabitants massacred, the

descendants of these Spanish horses were abandoned to wander over the desolated

country. They lived and bred for

hundreds of years by the laws of nature. Hunted

by Indians and wild animals, they learned to survive with droughts and a harsh

climate that allowed only the fittest to survive.

A Life of Danger

Almost four hundred years after the sacking of Buenos Aires, Tschiffely stood ready to swing into the saddle, determined to prove that the two weatherbeaten Criollos he had just purchased from Chief Liempichun, (“I Have Feathers”) were the legitimate descendants of Don Pedro Mendoza’s once-proud bloodline.

Local

horsemen who told the press, “The man’s mad,” can hardly be blamed for

their initial scepticism. Up till

then Tschiffely’s most gruelling task had been teaching in a posh school for

boys outside Buenos Aires. True, he

had knocked around the world, leaving home at an early age to immigrate first to

England, before taking the teaching job in Argentina.

But his only experience with expeditions of any kind had been acquired

from the safety of an armchair, as he read of the early exploits of the

Conquistadors and their equine companions.

His

lack of equestrian skills or exploration credentials never bothered him.

Remarkably self-assured, the slightly-built red-head balanced the

scepticism of his critics against his own need to discover the wild parts of the

South American continent. His plan

to ride Criollos to Washington D.C. was the natural outgrowth of his years of

research into South American Spanish history.

He wrote, “Eventually there was only one thing to do: screw up my courage, burn all the bridges behind me, and start a new life, no matter whither it might lead. Convinced that he who has not lived dangerously has never tasted the salt of life, one day I decided to take the plunge.

The plunge, as he so aptly put it, landed him in the saddle of two Criollo horses, Mancha and Gato, who proceeded to show their appreciation for having been picked to represent their breed by “trying to buck the guts out of me.”

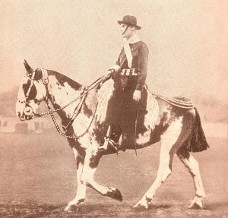

Mancha,

(The Spotted One), was a red and white piebald, 16 years old, who delighted in

attacking and kicking anyone foolish enough to come near him. His companion, Gato, (The Cat), a 15-year-old buckskin (dun),

was only slightly less murderous. The

two animals had recently been brought down from the wilds of the Argentine

pampas to a local estancia after a road march of more than 1,000 miles, in the

course of which they had lived on what little they could find.

Neither horse had ever seen a city, houses, automobiles or a stable.

They ignored the luscious alfalfa and oats put before them, instead

devouring with relish the straw put down for bedding.

These

equine savages were physically unattractive, having none of the finer points of

conformation that appealed to the haughty hidalgos of Buenos Aires.

Tschiffely

admits as much when he recalls, “Their sturdy legs, short thick necks and

Roman noses are as far removed from the points of a first-class English hunter

as the North Pole from the South. Handsome

is and handsome does, however, and I am willing to state my opinion boldly that

no other breed in the world has the capacity of the Criollo for continuous hard

work.”

Though

patriotic to the extreme, few of the proud Argentines could bring themselves to

believe that this inexperienced foreigner would live to prove his point, even on

horses they held dear to their hearts.

Wise Men Dare

In preparation, Tschiffely chose a traditional gaucho saddle, made up of a “light framework, about two feet long, over which is stretched a covering of hide. This sits easily on the horse and being covered with loose sheepskins, makes a comfortable bed at night.” A local pack saddle was found as well.

Equipment

for the extensive trip was kept to a minimum.

Tschiffely carried a .45 Smith & Wesson, a 12-gauge shotgun, a

Winchester .44, maps, passport, letters of credit, compass, barometer, woolen

blanket, light rubber poncho, goggles, a large mosquito netting which fitted

over his broad-brimmed sombrero. Additionally,

he carried a supply of silver coins in his saddlebags in order to pay Indian

guides who might refuse paper money.

On

the night before his departure, the intrepid horseman recalled that suddenly the

carping of his critics and his own inexperience caused him “to be assailed by

a sickly feeling, as if my stomach were a vacuum.”

Like many before him, his longing for adventure had brought him to the

point of no return. The historic

horseback ride which had previously sounded so thrilling, was now looming with

all its dangers, real and imagined, only a few hours away.

Word

had been leaked to the press the next morning, as he prepared to depart.

He consented to pose for them, alongside Mancha, who was to serve as

packhorse, and Gato, whom he proposed to ride.

Rain was falling and the roads leading out of Buenos Aires were already

hock-keep in thick, sticky mud. The

reporters regarded the whole thing as a huge joke:

“A lunatic proposing to travel overland to New York,” – ran one

story.

Years

later he recalled that after the press bowed and retired with ill-concealed

chuckles at his idiocy, he wanted to tell them, “Let fools laugh; wise men dare and win.”

But the rain was coming down harder and his own self-doubts kept his

opinions to himself.

Bad Roads and Worse

That first morning, a local stable boy had volunteered to ride beside Tschiffely and show him the best way out of town. The lad was mounted on a big thoroughbred which made the traveler’s stocky little animals look more diminutive than ever. After about an hour they came to a newly-made dirt road, and his guide informed him that by following it he would find his way clear to open country. His deed done, the boy turned his horse and headed home.

“His

thoroughbred was steaming with perspiration while my two Criollos showed no sign

of having traveled at all,” Tschiffely wrote.

The

rain gave him no chance to gloat over this first small victory. The countryside of Argentina was flat and desolate,

stretching as far as the eye could see in mile after mile of uninterrupted

monotony. There were no trees here.

The Indians called this tableland of grass the pampas – the open space.

Tschiffely, Mancha and Gato rode day after day across it, either baking

in the sun and sucking up the hated dust of the road, or slogging through

merciless mud when the skies poured down their rain.

Occasionally,

to his astonishment, an automobile would come plodding its way through the mud,

and more than once he was asked to assist in pulling these Tin-Lizzies out of a

mud-hole, a request he was obliged to refuse as his horses were not accustomed

to such work. Plus, he had already

grown a hatred for automobiles, as the drivers showed very little consideration

for him and his horses, seeming to delight in seeing the horses rear and plunge

when they passed.

“They

were my pet aversion from the beginning of the tirp to the end, and if all my

wishes had been carried out, Hades would be well supplied with motors and

motorists,” he wrote.

The

mighty pampas also brought him a peace of mind he had never known existed.

Day after day he rode in silence, alone in his thoughts.

The tranquil movements of the horses through this empty world rocked him

into a trance, like that induced by sitting too long beside running water or

moving tides. Here, in the

world’s emptiness, he realized he might have been at any place on Earth, at

any time in history since horses were tamed and ridden.

His critics lay behind him. Now

he was only a traveler under the open sky, looking for a place to pitch camp and

prepare his meal.

The Door to the Andes

Heading north, the trio trekked through mud-holes, over quicksand bogs and across rivers. Passing Rosario, Argentina, they travelled towards Bolivia. The landscape changed to arid, desolate wastes. Thick, white clouds of saltpeter dust blanketed the ground and choked the three of them, but didn’t slow their steady progress. By the time the caravan reached the town of Santiago del Estero, Tschiffely’s face was burned raw and his lips were cracked and bleeding.

The

maps he relied on were of little daily help, showing the topography in

frustratingly general details. Yet

asking the locals for directions could be just as fruitless.

“It’s

no use asking these people the way, for they have only one answer and will

invariably reply, ‘siga derecho no mas’ (just go straight ahead), although

the trail may wind and twist around a regular labyrinth of deep canyons and

valleys. If one enquires as to the

distance to the next place the monotonous and aggravating reply is always, ‘cerquita’,

which means ‘quite close,’ although there may be a whole day’s riding to

be done before one reaches the place.”

In

spite of these useless answers he made a point of asking every passer-by for

directions, even if it was only to break the monotony of lonely hours without

hearing a human voice.

Reluctant Friends

The one bright spot in this progressively more bleak landscape was the comradeship and trust that now developed between Tschiffely and his half-wild horses. Gato had tamed down quickly. When he found out that bucking and all his repertoire of nasty tricks to unload his rider failed, Gato became resigned to his fate and took things philosophically. Of the two horses, he was the more willing, being the type of horse, Tschiffely says, that if ridden by a brutal man would gallop until he dropped dead. His eyes had a childish, dreamy look. He also possessed a rare instinct for avoiding bogs, quicksand and deadly mud-holes, something his inexperienced ride soon learned to have complete faith in.

Mancha

was always alert, an excellent watchdog, who distrusted strangers and would let

no-one except Tschiffely saddle or ride him.

He completely bossed Gato, who never retaliated.

He had fiery eyes, which he used to scan the horizon constantly.

Of the two, he never ate too much.

By

this time both of the horses had grown so fond of Tschiffely that he never had

to tie them again. Even if he slept

in some lonely hut he simply turned them loose at night, well knowing they would

never go more than a few yards away and that in the early morning they would be

waiting to greet him with a friendly nicker.

In

a rare insight into his horses’ personalities, Tschiffely wrote, “If my two

Criollos had the faculty of human speech and understanding, I would go to Gato

to tell him my troubles and secrets. But

if I wanted to step out and do the rounds in style, I’d certainly go to

Mancha. His personality was the

stronger.”

Wicked Demons and Dangerous Cliffs

Journeying now through the mountains of Bolivia, the trio began to see that they had not even begun to suffer. They pushed their way through fast boiling waters and passed carefully over boulders larger than houses. Having already covered more than 1,300 miles, they came to the 11,000 foot high summit of Tres Cruses Pass. Tschiffely’s nose bled in the rarified air.

Hail

the size of small eggs beat down on them as they made their way through the

mountains. The broiling sun and

wind-driven sand forced Tschiffely to don a “sandstorm mask” and a pair of

goggles in an effort to protect his face and eyes from the harsh elements.

Upon entering an Aymara Indian village he was mistaken for a demon by the

superstitious natives, who fled at his approach.

After

travelling for more than three weeks at altitudes in excess of 11,000 feet they

reached the Bolivian capital of La Paz. A

policeman guided him to the local Argentine Embassy, where an astonished

ambassador and his staff received him with joy and hearty congratulations.

The ambassador had the good grace not to mention the fact that no-one had

expected him to arrive. Mancha and

Gato, however, “looked as though they had only been out for a morning’s

trot.”

A

brief rest lay behind them with full bellies and restocked saddlebags, when they

hit the trail once again. This time

their destination was Peru. They

soon entered Cuzco, the gateway to the ancient Inca empire.

The trails became so steep and rock that Tschiffely had difficulty making

it over the crest of the treacherous Andes mountains.

In cases where the trail became this dangerous, he first divided the pack

between the two horses. If going

downhill, he went ahead.

But

when climbing, he put Mancha in front and caught hold of his tail, in this way

being pulled along without much effort. He

learned always to use Mancha in front because he obeyed Tschiffely’s voice

commands and could be guided one way or the other. Gato was much too eager to go ahead to be of use in this

situation, pushing on until he was out of breath and preferring to pick a

straight route up the mountain, regardless of the obstacles.

The

journey had taken them from the plains of Argentina, over the mountains of

Bolivia and now brought them down into steep jungle valleys of Peru.

Hordes of mosquitoes plagued them. Despite

the heat, Tschiffely was forced to wear gloves to protect himself against the

blood-sucking vermin. In one

unnamed valley the horses were attacked one night by vampire bats.

The next morning, noting the listless condition of his weakened mounts,

Tschiffely took advantage of a local remedy and started coating the animals with

ground pepper every night.

Remarkably,

Tschiffely, Mancha and Gato were averaging 20 miles a day.

It was too early to congratulate himself.

But already he had journeyed further than his critics had predicted.

Then the trip came to a crashing halt.

Often

the track they had to travel was cut out of a perpendicular mountain wall.

On this day Tschiffely was luckily afoot, walking behind Mancha, with

Gato bringing up the rear. The

trail wound high over the Apurimac River, which from above looked like a winding

streak of silver. There had been

incidents when two riders happened to meet in such narrow, dangerous places and

the man who shot first was the man who rode on, for their was neither turning

back nor crossing each other in such a trap.

Mancha

was leading the way slowly along the giddy trail when Tschiffely heard a

stomach-wrenching noise from behind him. He

turned in time to see Gato lose his footing, shoot over the side of the cliff

and start sliding down the precipice.

“For

a moment I watched in horror and then the miracle happened. A solitary sturdy tree stopped his slide towards certain

death, and once the horse had bumped against the tree, he had enough sense not

to attempt to move. I took off my

spurs and climbed down towards him and as soon as I had reached the trembling

animal I began to unsaddle him with the utmost care.

Poor Gato was now neighing pitifully to his companion, who was above in

safety. It was not his usual neigh

– it had in it a note of desperation and fear,” he wrote.

Once

he had unsaddled Gato, Tschiffely returned to the trail and made preparations to

use Mancha to haul him up. A chance

passer-by oversaw the urgent rescue from above,

while Aimé returned down the cliff side to assist Gato.

“When

all was ready the horse was hauled back to safety but had it not been for the

fact that Gato spread his forelegs like a frog, he would have overbalanced

backwards, and the chances were that he would have swept me away with him.

My heart was palpitating so violently that I thought it would burst, but

once both of us were back on the trail that now looked like a paradise to me, I

looked through the saddlebags to see if there was a drop of anything to

celebrate the miraculous escape; however,

we were out of luck in that line and had to wait until we came to a spring,

where we washed down the fright.”

His

troubles were far from over.

Mancha Leads the Way

They

came to “the roughest and most broken country imaginable.”

Tiny trails led through winding valleys, across high passes and over little bridges spanning deep canyons. Some of the inclines they had to climb were almost heartbreaking, and he had to be very cautious not to overstrain Mancha and Gato. Lying below in the canyon were the bleached bones of burros and horses who had died trying to scale these mountains. Then landslides and swollen rivers made it impossible to follow ever this poor excuse for a road. He was forced to turn west into the Andes mountains again and hire an Indian guide to steer him through a country seldom seen by white men.

Though

Tschiffely rode, the coca-chewing Indian had no problem keeping up and in fact

often out-distanced the horses. After

some time he brought them to the most frightening bridge Tschiffely had ever

encountered.

“We

had crossed some giddy and wobbly hanging bridges before, but here we came to

the worst I had ever seen or ever wish to see again. Even without horses the crossing of such bridges is apt to

make anybody feel cold ripples running down the back, and, in fact, many people

have to be blindfolded and strapped on stretchers to be carried across,” he

recalled.

Spanning

a wild river hundreds of feet below was a bridge that looked like a long hammock

swung high up from one rock to another. Bits

of rope, wire and fiber held the rickety structure together.

The floor was made of sticks laid crosswise and covered with some coarse

fiber matting to give a foothold and to prevent slipping which would inevitably

prove fatal. The width was no more

than four feet and its length was more than one hundred and fifty yards.

In the middle the thing sagged down like a slack rope.

It was a horseman’s nightmare.

Upon

examining it closely, Tschiffely said he felt as if he had swallowed a block of

ice. He thought about turning back.

But his only other option was to wait many long months in some nameless

Indian village for the dry season. He

had no choice. They had to cross. He

instructed the Indian to take Mancha’s lead line and go ahead.

He caught the horse by the tail and followed behind.

“When

we stepped on the bridge Mancha hesitated for a moment, then he sniffed the

matting with suspicion, and after examining the strange surroundings he listened

to me and cautiously advanced. As

we approached the deep sag in the middle, the bridge began to sway horribly, and

for a moment I was afraid the horse would try to turn back, which would have

been the end of him; but now, he had merely stopped to wait until the swinging

motion was less, and then he moved on again.

I

was nearly choking with excitement but kept on talking to him and patting his

haunches, an attention of which he was very fond.

Once we started upwards after having crossed the middle, even Mancha

seemed to realize that we had passed the worst part, for now he began to hurry

towards safety. His weight shook

the bridge so much that I had to catch hold of the wires on the sides to keep my

balance. Gato, when his time came,

seeing his companion on the other side, gave less trouble and crossed over as

steadily as if he were walking along a trail,” Tschiffely wrote.

Through Deserts Extreme

The

next few days were a terror of torrential rains, slick trails and landslides.

Following their guide, the trio continued upwards.

The sun disappeared, leaving them chilled to the bone.

When the rains finally subsided, they pushed on, arriving at a small

village at the top of the world. Here

the guide left them, and Tschiffely, Mancha and Gato started their long, weary

descent towards the Peruvian capital of Lima.

It

was an arduous task to reach the city. On

the way he was careful not to contract “verruga”, a mysterious malady that

brought on frightful boils, swellings and death.

Finally, looking down from the top of a mountain, far below he saw a

train running through the canyon. A

sight, he recalled, that he had not seen for a long time.

On

the next leg of their journey water became scarce.

From the freezing mountains they had plunged down into the fiery hell

known as the Matacaballo (“Horse-killer”) Desert. The horses struggled and sank in merciless sand dunes which

rose one after another like huge ocean billows.

Outside the town of Ancon they passed through a battlefield where

soldiers from Chile and Peru had fought long ago. Once buried where they fell in the sand, the retreating

desert had now exposed its corrupt secret.

Bleached bones lay strewn about like old toys.

Leaving

the town behind, he still rode north, forsaking the trail and following the

coast.

Due

to the terrific heat, Tschiffely would start before sunrise, pushing Mancha and

Gato hard until the heat became unbearable, at which time they would seek

shelter.

“Journeys

through such deserts are trying in the extreme. At first the body suffers, then everything physical becomes

abstract. Later on the brain

becomes dull and the thoughts mixed; one

becomes indifferent about things, and then everything seems like a moving

picture or a strange dream, and only the will to arrive and to keep awake is

left,” he said.

Gato the Goat

Peru

finally lay conquered and behind them. In

Ecuador they entered the mountains and froze once again.

At one point a landslide had washed the trail away.

To turn back meant a detour of two or three long days.

But before them lay an eight-foot gap between both sides of the trail.

Mancha was the saddle horse that day and was going in front.

As the pack saddle needed readjusting, Aimé

walked back to Gato to do this before retracing his march.

He had been working for a while, when he glanced up and saw Mancha making

his way towards the spot where the trail was missing.

Before he could stop him, Mancha had jumped across to the other side.

“There

was no time for much thinking. I

tied Gato to a rock and then jumped across to do the same to Mancha, lest he

continue his dangerous wanderings. Now

the question was whether it would be safer to bring the one back or cross the

other. I unsaddled Gato, who jumped

across like a goat. I brought

across the pack and saddle by means of a rope, having to cross from side to side

several times to accomplish this primitive and ticklish piece of engineering.

Another fright, a good lesson and many miles saved,” Tschiffely wrote.

He

rode through Ecuador and on into Columbia.

The balance of the trip to Cartagena was a nightmare of water, lightning,

washed-out trails and dense jungle. He

had been in the saddle for almost two years and his initial boyish enthusiasm

was now tempered by the hardships he had weathered.

There were few silvery moons, balmy tropical breezes or wavy palms out

here. He was more likely to

encounter mosquitoes, sand-flies, suffocating heat, poisonous plants and

tropical diseases. He had long ago

learned that the need for constant vigilance frayed his nerves and doubled the

natural weariness of travel. Most

importantly he had discovered that a long horseback ride, which sounds so

thrilling in prospect, was in fact immensely wearisome and monotonous.

Yet

he never considered turning back.

The Young Pancho Villa

The Darian Gap of Columbia was a trackless jungle, so along with Mancha and Gato, he took ship to Panama. Here he was welcomed as a hero by the Americans in charge of the Panama Canal.

During

the course of his journey, Tschiffely had been sending letters back to friends

in Buenos Aires, never suspecting that some of his hastily-scribbled messages

were being printed in newspapers, or that they might appeal to a wide reading

public in both North and South America! His

fame was growing, though he was still totally unaware of any of these

developments. Instead, with more

than 5,000 miles of horrific travel already behind him, he was beginning to

believe he would see the trip through to the end.

The hearty American response in Panama helped justify that belief.

He

now made his way through the jungles of Central America, avoiding bandits,

poisonous snakes and hostile revolutionaries.

However, after crossing into Mexico, Gato went suddenly lame, and

Tschiffely, taking pity, shipped him to Mexico City to await his arrival.

Tschiffely and Mancha now marched north alone, past Tehuantepec, Oaxaca

and finally into Mexico City, where they retrieved their comrade.

In

northern Mexico, awash in revolutionary fervor, lawlessness and banditry, he was

forced to travel with a military escort provided by the Mexican government.

One night he was approached by a secretive man who asked him in a hushed

voice if he wished to purchase the skull of the infamous and recently

assassinated Pancho Villa. Before Tschiffely had a chance to say “no,” the man

produced what was obviously the skull of a child.

When Tschiffely pointed this out, the black-marketeer informed him,

“Quite right, Señor, this is the skull of Pancho Villa when he was a baby.”

Victory in Sight

At last the trail became easier. They crossed into the United States at Laredo, Texas and during their travels in that state were the guests of the Texas Rangers. They continued northward, past Oklahoma, the Ozarks, and on to St. Louis. From there the trio crossed the Mississippi and journeyed to Indianapolis, Columbus, across the Blue Ridge Mountains. Just short of their final goal an American motorist took deliberate aim at them, hit Mancha and sped away. Luckily the tough Criollo was unhurt.

“But

if I had still been armed,” writes Tschiffely, “which was never the case

after I crossed the US border, there is no telling what I would have done to

that man.”

At

long last, after more than three years in the saddle, the amateur horseman and

his two “old” horses arrived in Washington D.C.

Word of his remarkable travels had been sent to the National Geographic

Magazine, via the Argentine press, who now contacted Tschiffely about writing an

article regarding his trip. The

Ambassador from Argentina and other dignitaries took him under their wing.

His greatest coup was when President Calvin Coolidge threw open the doors

of the White House for him.

After

making a speech at the headquarters of the National Geographic Society, he

decided to ship Mancha and Gato to New York, rather than ride there.

There was too much traffic on the roads and he considered riding that

short a distance as “only a vulgar publicity stunt.”

In

New York, Major James Walker received him at City Hall and presented him with

the New York City medal in honour of his ride.

During the course of his stay there he booked passage for Tschiffely and

the horses back to Argentina on board the “Vestris” but they missed the

departure. The ship sank a few days

into her voyage with a loss of one hundred and ten lives.

Three weeks later he and the horses escaped the whirlwind of New York

society and boarded the “Pan-American”, sailing for twenty-eight days,

before finally docking in Buenos Aires, almost three years since their rainy

departure.

The Heroes of the Pampas Return

He returned to a hero’s welcome, this novice who the Buenos Aires hidalgos had predicted would die on the trail and embarrass their Criollo horses before international eyes. Now no praises were grand enough for the three heroes of the pampas. The Argentines, who had initially failed to support him, now took him into their hearts. They saw a reflection of themselves in Mancha and Gato. Like the tough Criollos, what they lacked in refinement and elegance, they made up for in vigour and independence.

Mancha

and Gato were pensioned off to an estancia in the south of Argentina.

Tschiffely’s book, “Southern Cross to Pole Star,” is considered the

most important equestrian travel book of the 20th century.

Since its publication in 1933, it has inspired countless equestrian

travellers to saddle up and explore the world from China to Canada.

In the mid-1930s Tschiffely rode across England and wrote about this trip

as well. Then in the 1940s he

returned one last time to Argentina to visit “my old pals.”

Though they had been running wild on the pampas since his departure,

Mancha and Gato remembered him and came when they were called.

As

he stroked Mancha’s mane he recalled their long ride, the climb to the top of

the Andes and the many challenges they had all three conquered together.

“I remembered sitting out there on a mountain all alone, my thoughts began to wander, as they had often done before when I was on some lonely Andean peak. The soft, cold, silvery light of the moon gave the mists below a ghostly appearance. I felt lonely but happy and did not envy any king, potentate or ruler. Here was I between two continents and two mighty oceans, with my faithful friends of thousands of miles both making the best of a bad meal beside me. But I knew they were satisfied, for the experience had taught the three of us to be contented, even with the worst."

To go to Tschiffely's official website, please click here.

For more information about Aimé Tschiffely's books, please click here.