Death Valley via Wild Rose Canyon

Lucy Leaf

|

|

Death Valley via Wild Rose Canyon Lucy Leaf

|

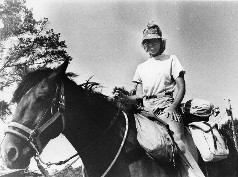

Lucy Leaf spent three years riding through the United States. In 1973 she and Karla Edmunds rode from Bethel, Maine to Missoula, Montana. The following year Lucy rode alone from Missoula, Montana to the Pacific Ocean in Northern Oregon, and then down the coast to Northern California. In 1975 she walked and packed her horse, Igor, in the Sierra Nevada range, across Death Valley to Phoenix, Arizona and then on to El Paso, Texas. In March 1976 she rode from the Guadalupe Mountains in West Texas to Northern Virginia via the Deep South. "While I did not record actual miles, or care much about miles covered," the Long Rider wrote to The Guild, "I figured I traveled about 7,000 miles with Igor. He was a 16.1 hand bay horse who was 5 - 8 years of age during the trip. I purchased him for $150, as he was recovering from shipping fever, from a dealer in Connecticut. He was retired in Maine and lived a healthy and active life until he died naturally at age 27."

“This is desert country. You need a support vehicle.”

No one would talk with me further on the phone as I tried to plan ahead how I would cross Death Valley, on foot, with my pack horse.

“And sorry, we don’t sell horse feed.”

This was just one segment of a long ride across the country, a return trip actually. This time I was headed east. With my horse, Igor, I had already traveled west for two summers, riding from Maine to Montana, and Montana to California, meandering on back rural roads to experience country that caught my intrigue. Igor carried me through the Adirondacks, along the Great Lakes, across the Great Plains, over the Rockies and the Cascades, and down Oregon’s Pacific Coast. Camping out was the way we lived. Except for the enormous amount of hospitality we received along the way, organized support and back-up vehicles were not part of the picture.

I had just packed Igor in the high Sierra Nevada backcountry for close to a month in late summer. Igor rested up while I took the opportunity to lead a string of mules back into the mountains for a pack station outfitting the first hunters of the season. My next destination was Death Valley. Intrigued by the open country of the Southwest, I was determined to travel historic routes, staying to dirt roads and trails as much as possible. With long stretches between re-supply, I was walking while Igor packed all the food and water we needed.

I knew from experience not to give up because people told me I couldn’t do something. I also knew not to head out into sparse country without knowing my next source of water and horse feed. So I did what I always did. I just showed up, arriving at a remote ranger station with Igor on the lead, my horse well-fed, well-shod, and well-packed.

“I need to know more about this jeep trail that goes through Wild Rose Canyon.”

“Ah, no problem. The jeep trail fades, but from there, just follow the burrow trails. There’s three good watering holes, can’t miss them!”

The ranger drew me a little map with three big “x’s” marking water holes. Filling my canisters with water at the station, I began the two day walk across the Panamint Range towards Death Valley. It was mid October, but the temperatures still reached into the 90’s on the valley floor.

I knew my water source, but feed was another matter. My next stop was the oasis resort at Furnace Creek in the valley itself. There were horses there. Something would work out.

Nevertheless, there was risk taking this back route. I had traveled a few days in the company of a rambling cowboy with a pack string of little mules carrying his life’s belongings. He said his name was Turk, just Turk. In his late forties, he did odd ranch work, a bit of horse shoeing, and supposedly wrote books. He looked well over 60.

“I know the desert, I live it, I can show you how”, he told me. He also kept a spare horse. So we rode together, off-road, exploring a ghost town and a remote little canyon where an underground river surfaced briefly, creating a little oasis with a few trees and a patch of green grass for camping and grazing. He made sourdough bread, very strong coffee, and slept in his bedroll out in the open, propped against his saddle, reading a book by a lantern. I slept in my tightly zipped LL Bean pup tent for protection from snakes, scorpions, and black-widow spiders. Igor stood directly in front of my tent, hobbled but free to roam, his draft-sized hoofs about 6 inches from my head. I woke up in the morning to his persistent nicker and nudges for the grain I kept in the tent.

As we approached the Panamint Range, however, Turk headed for the highway. I pointed out Wild Rose Canyon on the map. He said he wouldn’t take his stock through there. I decided to go anyway. There were legends of bandit gangs that once hid in that canyon.

“Look out for jacks”, he told me, “jacks attack geldings”.

Parting ways, I soon had an ominous feeling as the air became close, and a yellow fog-like cloud moved in. Suddenly the wind picked up, and though I had never experienced it before, I realized Igor and I were in a sand storm. All we could do was seek the lee of some large rock formations, the sand whipping all around us. Igor put his butt to the wind, and hung his head low, as he did in all inclement weather, standing rock still. In full acceptance, I did the same. It passed on quickly.

With an early start from the ranger station, the walk up over the Panamints was very pleasant. Finally, the whole of Death Valley lay before me, and I could see the road that led across the valley floor and a hint of the settlement that must be Furnace Creek. “No problem”, I thought. The jeep trail dwindled down to a well-traveled animal trail, as I expected. Burrow brays sounded here and there, which reminded me to pull out my tent poles in case of an “attack”. Noting a little water seep in a rock wall on the trail, I kept walking, the sunset casting exquisite soft hues over the range to the east. I figured I would camp near one of the water holes.

Soon, however, the burrow trails began splitting, and I became concerned I might miss an “x”. Then the burrow trails were going in all directions, with no main route anywhere. My anxiety rose as I kept descending towards the valley floor. Soon I figured I had gone too far, and needed to backtrack. With darkness closing in, and no evidence at all of a water hole, I felt panic creeping in.

“There’s a reason they call it Death Valley”, I thought. I knew I had to erase this thought from my mind and move into action. Tying Igor to a bush, I grabbed a container, and backtracked to the seep I had noticed, making sure not to lose my trail. Scraping at the grainy crevice with a knife provided a bare two cups of brown water. Igor was whinnying and pawing frantically when I returned to him as darkness settled in.

I set up a sparse camp high up from any wash, in a stark, rocky, and lonely place. All of Death Valley was a stark and lonely place. Stark and beautiful really, but I wasn’t so sure about the latter, in my current situation. Sleep was also sparse, with many sounds of the night.

Up and packing way before sunrise, I was intent on walking with the very first light. Igor got most of the remaining two or so gallons of water left. By early morning, the path had connected to the dirt road that led down into the valley and later, to the road leading across the desert floor. I thought we should be at Furnace Creek by noon. At mid-morning we were in the region of the “Devil’s Golf Course”, thankful for a road, as shards of limestone rose up from the earth for miles around us, like permanent hoarfrost, impassable to man or beast.

But the mountain range to the east didn’t seem to get closer, and the heat intensified. I couldn’t think about being thirsty. We just kept walking, and the road just kept going and going. I wondered if I had miscalculated the mileage somehow.

In the distance, I saw a dust swirl. In awhile, it got closer. It was a truck! I hoped it was coming our way. It did! Four men piled out, wearing work suits.

“We thought we’d see you today!”

“How do you know about me?”, I asked.

“The word is out, a gal traveling with a horse. We’ve been watching for you.”

I didn’t really want to mention I was out of water. Instead I asked about the distance left to Furnace Creek. Igor wasn’t shy however. He spotted the ten gallon water tank strapped to the back of the pick-up, and began nuzzling it, rather intently.

“I think you have a thirsty horse there.”

“Yeah, I’m afraid so. Couldn’t find the water holes I was planning on”.

From my canvas water bucket, he drank most of their water supply. I was given two cold Pepsi-colas and a candy bar.

The men told me the water holes probably got washed out by the flash floods they had a couple weeks earlier. They also said a man with a mule string had ridden in earlier, and mentioned that I would be coming through from Wild Rose Canyon. Turk didn’t linger though. It seems he had been there before, and was, perhaps, not too welcome.

“Desert rats, we call them”, one of the men offered. “We kind of help them on their way.”

“So, I guess I’m a desert rat too?”.

“Well, we haven’t got you figured out yet. You’re a bit different.”

Adequately hydrated, thanks to fast traveling word-of mouth, Igor and I walked into Furnace Creek later that afternoon in fine shape. A clear rumbling creek ran right through the resort. I set up camp in the shade of mesquite trees on the outskirts of the settlement, and bathed in the cool, clean water.

Still needing horse feed, I picketed Igor to graze the grass along the creek and made my way over to the horse corral, the place which had no horse feed for sale. Like any tourist, I chatted with some of the hands, sipped a cold soda, and simply hung out for a while. Observing the horses in the corral, I noted that one was more restless than the others, looking worried and anxious, and occasionally looking back at its flank. Then the horse broke into a sweat, showing increased discomfort. When the horse lay down, got up, and then lay down again, preparing to roll, I knew these folks had a sick horse on their hands.

Speaking to one of the hands who then spoke to another, I soon realized they didn’t know very much about the symptoms of colic.

“I can help”, I told them, “but first, I think you should call a vet.”

In the meantime, all the stable hands and I were doing everything possible to keep the horse on his feet, staying with him well into the night. Veterinary treatment brought relief finally, and later the resort manager said to me, “You saved our horse. You’re welcome to stay in the hotel, eat all the meals you want, make yourself at home!” He also offered me a job.

I told him I was just passing through, and what I really needed was some grain for my horse. I was glad to pay for it.

“Oh, you’re the one who’s walking with her horse! Give your horse all he can eat!" Igor and I enjoyed two splendid days of rest at Furnace Creek, fully fed and watered. I reveled in the stark beauty of Death Valley.

“And so”, I asked the man who had given us water from his truck, “am I a desert rat?”

“Not quite. We’re hoping you’ll come back. Isn’t it about time you started riding that horse?”

Main Stories from the Road page