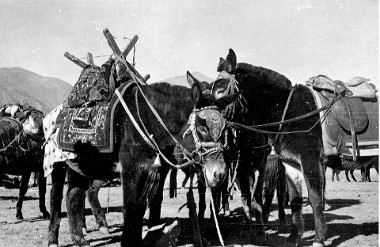

Tibetan Riding Mules

A Caravan Journey Across Tibet

by Thubten Jigme Norbu

|

|

A Caravan Journey Across Tibet by Thubten Jigme Norbu

|

In 1940, Thubten Jigme Norbu, oldest brother of the Dalai Lama and himself a reincarnated lama resident in the Chinese lamasery of Kumbum, traveled to Lhasa to visit his brother and family.

His family had moved to Lhasa during the previous year, at which time his brother was formally received in Tibet and invested with his titles as Fourteenth Dalai Lama. Thubten Jigme Norbu (or Norbu) had remained behind; he was a student at Kumbum and also had duties and properties there to attend to. His father's cousin, meanwhile, had traveled back to China; he had to escort Norbu's sister and her husband in turn to Lhasa, and he also meant to buy a number of horses at the Siling horse-fair. (The horses of Siling were both better and cheaper than anything available in Tibet, and Norbu's father was a collector of good horseflesh.)

Norbu wanted to rejoin his family; he asked his father's permission several times, meanwhile (for he was only a teenage student, after all) making the wildest plans to travel to Tibet on his own. His whole family was now in Tibet, after all! However, eventually his father sent permission, and Norbu's retinue plunged into preparations for the long journey to Lhasa.

This meant a four-month caravan trip, most of it through empty and debatable lands. In a few years, Norbu would be traveling via motorcar and airplane with complete aplomb . . . but for now, he had to deal with riding horses, pack animals, and protection against the threat of bandits. He would be accompanied by a retinue of twenty-one, all of whom needed equipment, tents and provisions. He ordered strong leather sacks, waterproofed by being rubbed with oil and fat; each would hold about seventy pounds of provisions. This meant either enough tsampa for one person for four months, or enough wheaten flour for four people, or enough hard rolls for two. His cook spent days baking huge quantities of these stone-hard rolls, which were made from a particularly nourishing dough and then fried in deep fat. They were quite small--barely bigger than cherries--so that when needed, they could be conveniently dropped into tea to soften before eating. The other provisions for Norbu's party were many and quite healthy: butter, dried vegetables, turnips cut into small pieces, beetroots, wooden tubs of pickled radishes, herbs and tea. Most people making the mountain journey to Lhasa also fetched along meat in their provisions, but Norbu refrained; his group would hunt along the way, and they would also be able to buy meat from the mountain nomads. (Though a devout Buddhist, Norbu had not been raised as a vegetarian; none of his family, good farmers from western China, abstained from eating meat.)

Since grazing along the way was severely limited, a sack of dried peas per animal was brought along as extra fodder.

With all these provisions, Norbu's modest party of twenty-two needed no less than a hundred and twenty animals for the journey. Among this number went forty riding-horses alone; on such a journey, one had to reckon on horses being lost, going lame or saddle-sore and needing replacement. Norbu's uncle, who traveled with him, was bringing a separate caravan of a hundred and fifty Siling horses, along with Siling mules which (like the horses) would be sold in Lhasa for a considerable profit.

| Tibetan Long Rider Thubten Jigme Norbu (left) is seen with his younger brother, Tenzin Gyatso, His Holiness the Dalai Lama. The two brothers represent the religious, cultural and equestrian traditions now threatened by the repressive Communist Chinese occupation of Tibet. |

All journeys along the great caravan route from Kumbum to Lhasa were undertaken, always, either in the summer season or the winter. Starting one's journey in spring or fall was out of the question; this had been the custom, Norbu wrote, for centuries. Many individual groups of travelers--such as Norbu's caravan and his uncle's similar caravan--would set forth separately, but join forces along the way. Thus, at last, they formed one immense, very slow-moving caravan composed of myriads of animals and men . . . but this was the way it was always done, and it meant safety from bandits and hazards, for safety lay in numbers. If an accident happened, one could be sure of having help at hand. Bandits were rife in the eastern Himalayas; during Norbu's youth, the threat of attack had never been far distant, and when he was a small boy the adults of his small village had once fought off armed invaders. Even the very largest caravans were sometimes attacked along the route to Lhasa. The bandits were experienced in guerilla fighting and there could be bloody losses. The best safety lay in numbers.

He left Kumbum on the nineteenth day of the fifth month (a lucky date, chosen for him by astrologers). The pack animals went out first; then Norbu, accompanied by his chosen companions, made a ceremonial leavetaking from his lamasery. He wore a good lambskin coat--a gift from one of his teachers, meant to protect him from the harsh upland gales of the Himalayas--and a monk rode behind him, carrying a large yellow umbrella which was the symbol of Norbu's rank. Lines of monks watched, some praying. Norbu was solemnly offered a last cup of tea. After he drank, the cup was refilled and let stand, a custom expressing the hope that he who left would soon return to drink the second cup.

They traveled a day to the Trekhog plain, twelve thousand feet above sea level. It was surrounded by wild precipitous mountains, watered by a single river; the only inhabitants were one or two nomads living in black hair tents. From them, Norbu's party bought milk and meat. When they lit fires, they had to use bellows to keep them burning. They stayed on the plain for three days, while other groups joined them. At the end of this period, there were no less than forty tents pitched in their company.

A second short journey--no more than several hours--brought them to Tongkhor, where there was a small monastery built on the side of a mountain. Here they stayed overnight. Three further days of travel brought them to Kokonor, the Blue Lake. They were now ten thousand feet above sea level. Norbu described the lake as enormous and brilliantly blue, surrounded by snow-capped peaks whose reflections shine in its salty waters. It was so big that to travel around it, would take no less than three weeks. There was a monastery on an island in the center of the lake, which was completely cut off for most of the year; the monks did not even own a boat. Once winter came, the lake would freeze over, and the monks would then tramp across the ice and beg for alms.

They stayed on the shores of Kokonor for a few days, during which time a number of other caravans again joined them. Then they undertook the week-long journey though uninhabited steppelands to the Tsaidam salt marshes. The steppes alternated with broken terrain and many watercourses, which had to be forded, and then there were high mountain passes to cross over. All the flat terrain was undermined everywhere with the burrows of the 'rat-hare' or marmot; the travelers were constantly breaking into rat-hare holes, and the rat-hares themselves (they were completely tame) sat watching and kept up a concert of whistling throughout. (Another nickname for marmots was 'piping hare'.)

Tsaidam, on the far side of the mountains, was an enormous area of marshy plains. It was dull and gloomy compared to the steppes, which were covered with bright vegetation: yellow, brown, red and purple. They skirted the eastern edge of the marshes, and came at last to the great nomad camp of Tsaidam, the last caravan assembly point along the way.

Here was a town composed entirely of tents. There were merchant caravans, groups of monks going into Tibet, and families of nomads making the holy pilgrimage to Lhasa. Final preparations were made for the journey, and any last-minute repairs too. The tent city buzzed with activity from dawn till long after dusk. There was such a hubbub that it was often difficult to hear yourself speak. The nomads who came to this camp regularly, sold butter and milk and meat to the travelers. Norbu bought a dozen sheep for his group; these would be driven along with his pack yaks and be slaughtered at need. Along the shore of a nearby salt lake, men were breaking up the thick saline crust and putting pieces in bags to take along on the trip. When night came, Norbu had a tent to sleep in, as did the wealthiest and best-connected travelers; everyone else slept outside, wrapped in coats and blankets, and every little depression in the ground became a valuable impromptu shelter. (The winds in the northern Himalayas are notorious.) The servants and herdsmen usually built a kind of square from the loaded bags, lit a large fire in this shelter and huddled around it. When the cold struck home, relays of hot tea would help keep them all from freezing.

By the time they set forth from this last stop, there were a thousand travelers all heading for Tibet. And with them went twenty thousand animals altogether.

This vast caravan moved in a kind of multi-species leapfrog, day after day, as they crawled slowly deeper into the Himalayas. First went the yaks with their burdens, setting forth at midnight and grazing along the way. (Everyone else caught up to them before reaching the next campsite.) About two o'clock in the morning, the rest of the caravan began to prepare to move. The horses were saddled and the pack animals--mules and horses--were loaded . . . while Norbu usually lay snug in his tent, unable to force himself out into the icy pre-dawn wind till the very last moment. Then he hurried out and saddled his horse, while a companion struck his tent and loaded it on a mule. All this happened by whatever feeble starlight or moonlight the weather might offer.

Each herdsman had twelve beasts plus his own mount to attend to. They worked in pairs to load the animals: each animal carried two equally heavy saddle-bags, which were fastened cleverly together and needed only be lifted onto the animal's back. One herdsman fastened a strap under the beast's belly, and then all that needed to be done was to unfasten a hobble, slap the pack animal smartly on the haunches, and off the creature went, eager to join the rest of the herd. And the two herdsmen would go on to the next animal. (The leading animals were fitted with belled collars.) In barely half an hour from start to end, the whole main caravan would be on the move. The horsemen always moved in the rear of the pack herd, each rider leading two spare horses.

| Yak Caravans such as this one became

part of the immense caravan crossing Tibet in 1940. Click on picture to enlarge. |

Behind them, only the cooks and scouts remained at the campsite--more than forty cooks and scouts, for a group of travelers as large as the one Norbu went with. The cooks had no morning chores, for they always packed up their utensils the night before; the main caravan had set out with empty stomachs, not even pausing for tea. The scouts collected the pegs and ropes to which the beasts had been tethered the night before and loaded them on particularly powerful mules. These wore bigger collars than all the other mules, and louder bells on those collars, with scarlet bobbles of yak-hair for extra decoration. Once this was done, off went the scouts, riding side by side with the cooks. The best horses were given to them, because they needed good fast mounts. They would leapfrog the whole caravan during each day's march. It was the scouts' work to pick out the next campsite, and it was the cooks' job to have hot tea and a bite of food on hand when the caravan arrived.

The usual camping place would be a site where innumerable other caravans had camped in other years. Stones would have already been gathered in circles for fires, and the animals of the previous caravans would (hopefully) have left plentiful manure for cooking-fuel. (In central Asia, most of which is treeless steppe or desert, dried dung was the most common fuel.) By the time Norbu rode in--having spent five or six hours in the saddle--the tether rope for his pack animals would have been pegged out, ready for use. His caravan-cook would have steaming hot tea prepared; this was the more welcome, because it would be the first hot drink Norbu enjoyed since the evening of the previous day. Hopefully, his particular camping place would be a desirable one, one which other caravans' scouts had not managed to claim before his own group's scout took possession. (The most experienced scouts invariably managed to stake out the best campsites, those with the richest grazing and the shortest way to water.) The animals would be unloaded and released to graze for the rest of the afternoon. Fuel would then be collected for the camp-fires: roots, tamarisk branches, thorns, and of course any dung available. Everyone helped collect the fuel. Everyone then gathered for a quick meal; they enjoyed tsampa, dried cheese and perhaps a bite of meat, all washed down with good hot tea. Everyone then set to and checked all the caravan equipment, and repaired everything that needed it. Once darkness threatened, the animals often showed up on their own, coming in from whatever grazing-grounds were nearby and demanding their evening ration of dried peas, which was fed to them from nosebags. The travelers fed their beasts and tethered them for the night. Because Norbu had not stinted in preparing for his journey, his beasts were tethered with the best rope--woven from the long individual strands of yak-tail hair, with shorter lengths of rope with wooden pegs spliced onto it at intervals, for fastening the individual animals. The four big pegs which held the main rope in place were specially made, of the toughest thornwood and rosewood which had been hardened with oil and then dried in the sun; the upper part of each peg was wrapped in thick pelt, which protected the expensive rope from fraying. Norbu had even had reserve pegs made, in case of breakage.

Finally, once the pack animals were settled, the human beings could then eat a square meal (they usually got meat, more tsampa, rolls, and--of course--still more hot tea) and then turn in. They all went to bed as soon as darkness fell. The horses would be protected with saddlecloths against the cold, the mules would be more lightly protected by their loosely strapped-on saddles. The yaks, being indigenous to the Himalayas, needed no protection. The baggage had been piled up in a wall against the wind. Finally, the dogs with which no caravan would embark, were tied up to the corners of the baggage-wall. (The dogs were probably Tibetan mastiffs, enormous black creatures bred for protection against bandits and attacking wolves--so hairy and so formidable, that non-Tibetans often mistook them for bears.)

Days went by in this manner. Norbu saw the wildlife of the Himalayan steppes: vast herds of drongs or wild yaks, so many that when they put their heads down and all charged together at the gallop, the earth shook and great clouds of dust filled the atmosphere. At night the drongs huddled together against the cold, standing in a ring with their calves in the center. During snowstorms, they would press so closely together that the condensation of their breaths rose in a sort of steaming column. The nomads hunted them; their flesh was considered delectable.

The kyangs or wild asses of the steppe could also be seen by the thousand. They lived in smaller herds than the yaks: each herd consisted of one stallion with a harem of from ten to fifty mares. When they ran, they ran like arrows, light brown on their backs and pale-colored on their bellies, with long thin almost-black tails; they stretched out their necks and their tails streamed behind them, and they were a magnificent sight. The autumn was their rutting season. They were very curious and often surrounded the caravan, neighing at the caravan-animals and sometimes goading the pack beasts into flinging off their loads and galloping off after them. Some of the pack animals ran off with the kyangs and were never seen again, their packs lost forever as well.

Their enemy was the steppe wolf of Tibet. If they spotted a wolf, the kyangs would form a circle, put their heads down in the middle and kick out wildly behind them. Norbu also often saw the native bears called rat-hare bears, whose major source of food was the rat-hares or marmots. They would dig the rat-hares out of their burrows, while steppe foxes prowled around nearby--waiting for unearthed rat-hares which might come bolting in their direction, tasty morsels on the run. The caravan climbed over mountain passes. The highest pass they had to tackle was across the Burhan-Buddha Mountains, and they rested the animals an entire day beforehand. They began to climb the pass at nightfall, and reached the summit at midnight, at which point the cold took their breaths away; still they kept on all night, finally descending to an altitude where they could find water and grazing; then they were so exhausted that they rested another entire day. Everyone complained of breathlessness on the summit, and of intense dizziness. This was the malady which Tibetans used to call pass poison--poisonous vapors emitted by the heights, which robbed travelers of their senses. One chewed a clove of garlic as a traditional remedy; many riders also sat backward on their horses, so as to face away from the icy gusts of wind. It used to be said that the passes on the outskirts of Tibet were guarded by protective spirits, which sent pass poison with especially virulence upon foreigners and invaders. It was, of course, altitude sickness.

They forded rivers. Their scouts picked out the best fords for the animals, which had to swim across. As they did, the water downstream was transformed to brown mud thick as soup, from the thousands of hooves stirring up the river-bed. Every time they forded a river, they halted on the far side and checked all their baggage to see if the water had gotten into anything. Whatever was damp, had to be unpacked and put in the sun to dry. If the river was in spate, all the travelers had to dismount, strip naked and tie their clothes in bundles on their backs, and wade across clinging to the manes of their animals.

Throughout, the people of the caravan had to keep a weather eye out for the local tribesmen, many of whom doubled as ferocious bandits and robbers. Summer gave way to autumn.

Finally—and only after all this—they came to the Tibetan frontier and the border-guards which manned the outposts there. All the wild territory they had been traveling through, was debatable land and inhabited only by the nomads, who owned allegiance to no country and no government. They had been on the road for four months straight. At last, they had reached the realm of the Dalai Lama.

This “Story from the Road” is extracted from the book, “Tibet Is My Country” by Thubten Jigme Norbu

Main Stories from the Road page