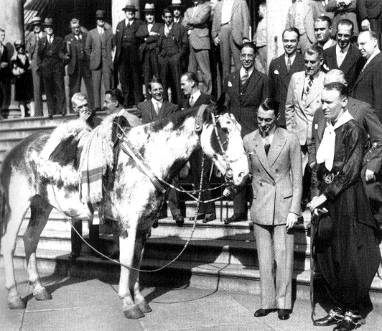

Aimé Tschiffely and Mancha being greeted by the Mayor of New York

Danger and Death in the Saddle

Basha O'Reilly FRGS

|

Aimé Tschiffely and Mancha being greeted by the Mayor of New York |

Danger and Death in the Saddle Basha O'Reilly FRGS |

While I was writing this article, the English Long Rider Christy Henchie was killed in a horrific traffic accident. Her travelling companion, Billy Brenchley, and their horses were seriously injured. The couple were making the first journey across Africa, from the north to the south.

They had crossed the Sahara desert, transporting their horses down the Nile in a barge, and survived the civil war in the Sudan – when their dreams were destroyed in Tanzania.

|

Christy and Billy at the start of their journey, Cap Blanc, Tunisia |

They were leading their horses on a quiet road when they arrived at a small village. A crowd of curious villagers greeted them. Then disaster struck

The impatient driver of a bus smashed into the victims. Christy and two Tanzanians were brutally killed. Billy and 25 of the villagers, including several small children, were seriously injured.

It was the worst accident in the history of equestrian travel.

A shocked journalist said, “I thought the greatest dangers for a Long Rider were bandits or bears.”

He was wrong.

The greatest danger is a driver.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, horses and mechanised vehicles shared the road. It was less dangerous to be on horseback at that time for several reasons. There were many more horses. There were fewer vehicles, and they went very slowly. And the drivers respected the needs of horses.

During the twentieth century there were more paved roads. This encouraged the creation of more vehicles, which went more quickly. As the speed increased, the links with horses lessened.

It is often necessary to ride along a road, and one can get lucky.

When Christina Dodwell rode across Kenya in 1978, she asked a tribesman if there was any traffic. “Certainly,” he replied, “A car came by fifteen years ago.”

But we can’t all turn the clock back or travel in Kenya.

The journey of the best-known Long Rider of the twentieth century was halted by a car.

When he set off in 1925, it was Aimé Tschiffely’s intention to travel on horseback from Buenos Aires to New York. In Latin America he survived jungles, bandits and a revolution. The greatest danger awaited him in the United States. Between Texas and Washington DC his horses were deliberately hit twice by murderous American drivers.

So Aimé decided that the danger was too great. “I had originally intended to finish this long ride in New York City; but after two fairly serious accidents, when I was deliberately run into by automobile drivers, I decided it would be better to end it in Washington, having ridden from capital to capital. I did not feel it sane to expose my horses to further danger and possibly even to lose them.”

Aggressive motorists have no nationality. They are impatient tyrants encased in a steel cocoon. They have a feeling of personal power and think themselves anonymous and invisible. Studies have shown that many drivers are convinced that the road is theirs alone.

| Long Riders report that more and more lorries fly past, almost touching them. |

The best defence is to remain always vigilant: as Shakespeare wrote in Hamlet: “your best safety lies in fear.”

Most drivers know nothing of your existence. Driving has become so boring that most of the time they are daydreaming, drinking coffee, eating, listening to the radio or chatting on their mobiles. They do not expect to see a horse.

After more than 10,000 miles in the saddle during four journeys in North America, Long Rider Bernice Ende has personal experience of the dangers of traffic.

| This dead horse in Phoenix, Arizona, proves that the greatest danger comes not from bandits and bears, but from murderous drivers. |

“American roads are very dangerous. It only takes the unexpected appearance of a bird, and even a calm horse can shy. Suddenly you find yourself in front of a lethal lorry.”

It is not only aggressive drivers who pose a threat. Sometimes it is their naïveté which puts us in danger. English Long Rider Keith Clark learned this lesson during his journey in Chile. “I was on a road full of lorries. One of them had slowed down and given us plenty of room. I thanked him with a wave; he replied by blowing his horn when he was beside us.”

Keith was almost killed when his terrified horse reared up, jumped over a wide ditch and galloped towards a barbed wire fence.

So, you have everything ready. You are riding a well-behaved horse. The weather is good, you and your horse are highly visible. You have chosen a road with wide verges. What have you forgotten?

Who is coming towards you?

Anybody, in any country, can become impatient and dangerous behind the steering wheel. But the age and the sex of the driver can influence your safety. Young people have more accidents than their parents, and it is a hundred times more likely that a young man dies in a traffic accident than a mature woman.

So to reduce the risks, try to make eye contact with drivers as they approach. Do not hesitate to wave at them to ask them to slow down. Keep an eye on the road ahead to see if there are loose dogs, children, or anything which could frighten your horse and cause him to shy.

There are times when the safety of your horse obliges you to avoid an urban nightmare.

When Keith was approaching Santiago, the capital of Chile, he faced 35 miles of deadly traffic. So he had the horses transported across this horror in a lorry. “There is nothing ‘pure’ about asking the horses to travel along so many miles amid this traffic and pollution,” he wrote.

Because the mechanised world has become a planetary reality, generations of Long Riders have scarcely survived a deadly encounter between horse and driver. So mounted travellers have to be ready to face murderous drivers and dangerous roads.

The information in this article is a very small extract from the chapter on traffic which appears in the “Encyclopaedia of Equestrian Exploration” by CuChullaine O’Reilly.

Main Stories from the Road page