The Grey Scourge

Hair-raising Romanian wolf stories!

by Rook Carnegie, of Braila, Roumania

(This article was first published in The Wide World Magazine in 1910.)

|

|

The Grey Scourge Hair-raising Romanian wolf stories! by Rook Carnegie, of Braila, Roumania (This article was first published in The Wide World Magazine in 1910.)

|

Harmless and cowardly in summer, when he hunts alone and there is plenty to eat, but a deadly menace in winter, when hunger gnaws at his vitals and he joins his grey-coated fellows in concerted attacks upon hapless travellers - such is the dreaded wolf of the Carpathian forests. In this article, Mr. Carnegie, who has lived in Roumania for many years, tells some enthralling Christmas stories concerning life-and-death fights with the "grey scourge."

In England the worried mother, in order to make her child keep quiet, threatens it with, "If you are not good I'll give you to the sweep!" In Roumania the peasant mother says, "Be quiet, or the wolf will come and take you!" And it is not only the children of Roumania who fear the wolf, for its presence is a terrible menace to old and young alike, A fearful coward in summer, when he has plenty to eat and lives alone, it is only in winter that, emboldened by strength of numbers and desperate from the gnawings of hunger, he becomes a savage and ruthless beast of prey. The trackless forests of the Carpathians teem with the grey brutes, and thence in winter they come down to the plains in search of prey, travelling hundreds of miles across the frozen wastes, attacking and devouring anything and everything that comes in their way. For this reason all livestock is kept under cover throughout the whole of the winter.

Even in the daytime the peasants move from village to village only in large, well-armed groups. Every winter the newspapers are full of accounts of encounters with wolves or deaths from their attacks. The annual quota of the latter must always run into three figures. Organized " drives" are sometimes made, but with small success so far as the wolves are concerned, instinct apparently warning them to save themselves ere the network of beaters is drawn too close.

In times gone by they were more numerous than at present. Even in the larger towns no one stirred out alone after dark, as the marauding brutes often penetrated to the very middle of the town itself. In Tulcea, on the Lower Danube, there exists the tale of how, many years ago, some thirty people, guests at a wedding, started for home in the small hours, with gipsy music in front, to conduct each family in turn to their dwelling. None of them arrived home! I have been assured by several inhabitants of the town that this is absolutely true, and I fully believe it to be so. One can imagine the size of a pack that would dare to attack and kill a party of thirty people.

The following three stories I can personally vouch for, as the particulars show.

* * * * * *

The winter of 1901 was an exceptionally severe one. So heavy was the snow that on one occasion the train service was interrupted for ten days, during which time we received no word from the outer world.

Five privates of the 6th Regiment of Militia, with its headquarters in Galatz, obtained leave of absence for the Roumanian Christmas (our 7th of January). Their names were: Vasili Stan, Vasili Omescu, Ghitza Maorodin, Ilie Stephanescu, and Alexandru Balceanu, all belonging to the village of Pekie. On the 7th of January, their Christmas, they set out for home, a distance of from five to seven miles.

The three days' leave expired, and all those who had been on leave reported themselves with the exception of our five. They were marked as not having returned to barracks, and after a week's time were regarded as deserters, and warrants were issued for their arrest.

On the military authorities inquiring at the village, however, they were surprised to hear that the men had never arrived there. The matter was given over to the police, but though a hue and cry was raised and their description circulated throughout the country, nothing could be heard of them.

A fortnight later some peasants with sleighs went to collect firewood in the woods lying between Galatz and the village of Pekie. On the outskirts of the forest they came on a terrible sight, and reported it at once to the mayor. I was stopping for a few days with a landed proprietor in the neighbourhood, and so heard of the affair. My host had horses put in the sleigh and we drove over. Everything remained as the peasants had found it, waiting for the military authorities.

The snow inside a circle of thirty yards was beaten and trodden down, soaked a deep crimson with frozen blood. Buttons and five sword-bayonets, with blood frozen deep on the blades, one of which had a portion of the vertebra of a wolf’s backbone still on the point, lay about. There were also scabbards and belts, much gnawed, some few human and wolf bones, scraps of cloth, and - five pairs of feet! For wolves never eat the feet of their human victims, which fact I have never yet seen noted in print.

It was not much, but enough to tell us what had happened. The poor militiamen - tramping happily over the frozen snow, carrying their little presents for those at home, joining, perhaps, in one of their patriotic songs - Iittle thought of the unseen enemy treacherously skulking along in the undergrowth on their left, watching for a favourable opportunity to make the final rush. Then came the sudden attack, the fierce fight for dear life - fists and bayonets against those terrible sharp fangs. And at last the end, one after another being pulled down, with the final fight among the pack, those killed by the soldiers being also hungrily devoured.

Some of the peasants had reverently fixed up a holy candle or two, and a few of their relations were praying on all fours - the peasantry of the Balkans do not kneel.

* * * * * *

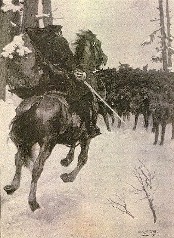

It is not often that a man lives to tell the tale of escape from these four-fooled fiends of winter, but here is a tale by one who fought an immense pack single-handed and saved himself by coolness and bravery.

On December 24th, 1903, Barbu Calinescu, a sergeant of the rural gendarmerie, was returning to the town of Ploesti, having been on his weekly patrol through some of the outlying villages. I will give his story as nearly as I can as he lately retold it to me.

“It would be about five and getting dusk as I came along the road where it cuts into the edge of the forest of Vadeni. My horse began to get a bit restless, but I did not attach any importance to its behaviour till it began to snort and shiver. Then I heard what the animal had heard - the far-away baying of a pack of wolves. I knew what it was, though I had never heard the sound before. My charger began to get very nervous, and for this reason I commenced to trot - not that it ever struck me for a moment that they were after me. After a time the sound died down, and I supposed the brutes had gone off in some other direction. Suddenly, however, it broke out again from the forest on my left, this time very much closer. Then I heard the crackling of broken twigs, and soon the baying appeared so near that I wondered I could not see some of them.

| Sergeant Barbu Callinescu,

who found himself surrounded by a huge pack of hunger-maddened wolves, and

only narrowly escaped with his life. Click on picture to enlarge it.

|

Never thinking of danger - for he who rides always feels safe on his horse - I unslung my carbine, meaning, when I got a look at them, to give them a fright, expecting one shot would send them flying. We always carry two blank cartridges above three bulleted ones in our carbines.

I had not long to wait. A minute or two more, and I saw weird grey shapes flying along among the under· brush and between the fir trees; as they got nearer their numbers increased, and I could barely keep my terrified horse at a short canter.

Presently, as though at a preconcerted signal, they all showed themselves; I should think there were two hundred at least! Taking up my reins, I fired my two blank cartridges, but, to my consternation, the reports had no effect on the brutes! Now, for the first time, I began to realize that the matter was serious. Looking behind me, I saw some of them crossing the road, so as to hem me in on both sides.

Then I fired my three bullets at them – bang! bang! bang! I heard yelps of pain, but what damage I had done I could not see, for by this time I was galloping. Slinging my carbine strap over my head, I sat down to ride hard. The road here was straight, and I looked anxiously ahead in the hope of seeing some carts or other signs of human presence. But there was nothing to be seen! I knew now that I must make a fight for my life. I had a good hour to ride, going my best, before I could hope to reach a place of safety. There was no need to spur my steed; the poor beast was snorting and sweating with fear as he dashed along. Happily I managed to keep him in hand: had he lost his head and gone rushing away into the woods it would have been adieu to both of us!

Now, for the first time, they came close to me. Eight or ten great brutes leapt out into the road and raced along, looking up at me; and to my dying day I shall never forget their cruel red eyes. The great danger, I had always heard, is when they jump at a horse's shoulders and fix on with nails and teeth, driving their victims mad with fright and pain. Against this, I knew, I must be on guard. Presently one ran forward, clear of the others, looking up and obviously preparing for a jump. I leaned forward and gave it a revolver bullet. With a yell it sprang into the air and dropped. Some few rushed at it, but, as I said before, I was galloping just as hard as my horse could go, so I did not see if they stopped to eat it. They were now flying along all round me - regularly, steadily, making hardly a sound. This noiseless manner of rapid progression - gaunt, red-eyed brutes waiting their chance to pull me down to death - was most terrifying.

We fairly flew along. Happily the snow was neither too hard nor too soft, and gave good foothold, for had my charger stumbled we should both have been finished.

Again one made a rush then two others. Each time I bent forward and, shooting carefully, dropped each in turn at close quarters as they approached my horse. I had only two more bullets left, and they soon went in the same way - six cartridges, six wolves.

Presently, to my amazement and joy, the pack dropped back and disappeared from sight. Had the shooting been too hot for them, and were they cowed, I wondered? I did not relax my pace at first, but, hearing nothing, I finally slowed down and allowed my panting charger to walk. At last, however, as the light was getting bad, I broke into a trot again. I was just turning a bend in the road when, with a gasp, I realized the cause of the wolves' sudden disappearance. The cunning brutes had cut off a corner and were waiting for me; the road was black with them!

I had no more bullets, but I had my sabre, and glad I was then to think that I knew how to use it. There was nothing to do but to charge them, I decided. To diverge from the road meant certain death; to keep straight on was my only hope.

|

Suddenly my horse gave a scream and a leap that nearly unsealed me. A wolf

had sprung on to his quarters; I turned in my saddle and, as it was too

close to cut, I brought the heavy hilt of my sword down on its head with all

my strength. I heard the skull crack. It dropped off - dead, I suppose - and

on we flew.

Click on picture to enlarge it. |

My poor charger was panting and groaning with fear and the hard going, but there was no stopping. Using my spurs freely I dashed on, and almost before I had time to think the wolves were all round me. Sword exercise! I went through it with a vengeance during the next few minutes! It was slash, slash, slash, right and left, as wolf after wolf tried a leap at my charger's shoulders. But I was soon through them and racing along again - with the pack thinned a little, I tell you - on each side of me.

Suddenly my horse gave a scream and a leap that nearly unsealed me. A wolf had sprung on to his quarters; I turned in my saddle and, as it was too close to cut, I brought the heavy hilt of my sword down on its head with all my strength. I heard the skull crack. It dropped off - dead, I suppose - and on we flew.

My poor horse was sobbing now, and I felt every stride was an effort. It seemed cruel to spur, yet I had to for both our sakes. Soon he began to flag. Would this awful race never finish, I asked myself despairingly. Then, all in a moment, as though by an order, the pack dropped back, trotted, and turned. Was it some trick of the devils to catch me?

I kept on, but they did not follow me. Then I looked ahead and saw lights. Thank Heaven, I was nearing the outskirts of the town! In the excitement of the race I had had no time to note any landmarks. My charger dropped to a walk, panting, and with head hanging down. With trembling fingers I tried to return my blood· stained sabre to its scabbard, but, now that the excitement was over, my arm was too tired, and I could not raise the point sufficiently high.

The people in the cottages on the outskirts gazed at me in wonder. At the barrier I stopped, and the policeman outside the office came over. He told me afterwards that he thought I was drunk. I got down, but went lurching all over the place, finally staggering into the office and dropping on a chair. They got me wine, and that freshened me a little. They would hardly believe my story, but my sword and some nasty bites on my horse's shoulders and flanks told the tale. I had been about an hour over that ride; it seemed like a month. I have often been over the ground again by day - and sometimes in my dreams.

Next day four of us, with plenty of cartridges, went along the road and found remains of wolves and the marks where they had eaten their dead brothers. That same evening, not far off, a peasant and his two horses were attacked and devoured - no doubt by the same pack.”

* * * * * *

Of the many wolf stories I have heard, the following is by far the most romantic. It was told me some years ago by the mayor of the village of Borcea Verde, a village in the Carpathians. If anyone looks at a map he will see the sources of the River Tekete on the Hungarian frontier and the Chuzzitza on the Roumanian side. Between the two lies the village in question. We had been shooting all day, and, sitting down after long toiling among the mountains, the subject of wolves came up. A certain Belgian engineer, who was of the party, gave it as his opinion that no wolves would stand against a bold front. Various tales were told to disprove this, and finally our host for the night, the mayor, gave us the following.

“A few years since, gentlemen, there lived in this village a girl named Katinka Gaitan. She was a great beauty, very fair and blue-eyed, like many of the Mokanch (a word meaning the women of the Roumanians settled in Hungary). Her father possessed some forest land, and some dealers from Budapest came and bought up all the timber, and so he became the richest man in the village, Therefore Katinka was a great parlie - a good catch, for she was the only child and would inherit everything, But, if pretty, she was a terrible coquette, always leading some young fellow on and then throwing him over for another. At last, however, something happened that taught her a lesson. One day two of her suitors got to words about her, and one, losing his temper, drew his knife and struck the other.

Then there was a fine row. First the gendarmes came, and then the “Procuror” (Public Prosecutor). It looked like being a murder case but the wounded man got over his injury in time, and the other - Ilie Pantu, son of a very well-to-do man - bolted, no one knew where.

From that time Kalinka seemed an altered being. There were no more flirtings, no more standing about with the other young people of an evening; nor did she join in the "Hora" and other national dances on Sunday afternoons, though she was considered one of our best dancers. She remained at home, working with her mother. The Katinka of before was not the Katinka of now, people said. So, gentlemen, three years passed away, and on the few occasions we saw Katinka she was quiet and staid, and we thought her more beautiful than ever.

Then we were all surprised one day at being invited by her parents for the following Sunday to her "logodna" (betrothal ceremony), To whom? we asked one another.

There was in the village a very quiet and staid young fellow named Radu Patricin. He was an orphan, living in his own house, which he had inherited, with only an old woman to look after him. He was a "venator," or professional hunter, trapping foxes and other animals for their skins, and shooting game, which he disposed of to the Jew traders. He lived very simply, and it was known that he saved money; but whoever thought of Radu as a husband for Katinka?

Well, we went lo the "Iogodna," ate and drank, played cards, and danced all night, leaving at daylight, wishing prosperity and happiness to the young people. But we knew it was only a marriage of arrangement - got up by Katinka's uncle, who owed money to Radu - and that, so far at least, there was not much love.

The "logodna" was on December 1st, as I remember, like all of us here in the village do, only too well.

A fortnight later who should ride into the village but llie, the man who had, three years before, stabbed the other in the quarrel about Katinka.

He came in the gay uniform of a Hungarian hussar, mounted on a splendid grey charger, and with a "wachtmeister's" stripes on his arm.

His parents received him with open arms. All the past was forgotten, and nothing was too good for him; you see, they were "Mokani," and so actually Hungarian subjects. Ilie was the hero of the village. Every day saw him at the "caritchima," paying for wine for everybody, whilst he recounted to the open-mouthed idlers the wonders of Budapest and Kecskemet, where his regiment was stationed.

No one saw them meet, and so everybody was surprised on the following Sunday, when Katinka came walking to church between Radu and Ilie.

Then, very soon, we began to see Katinka and Ilie alone, and began to remember how, in the old days, IIie always seemed the most favoured of the crowd of Katinka's followers. But, as Radu was out with his traps and his gun all day, he was the only one who saw nothing, and nobody cared to be the one to tell him - only everybody hoped llie's leave would soon be at an end.

Christmas Day, as we reckon it, came round, and then something happened. We were able to put two and two together because we found, afterwards, a trap in the snow - fixed, but not yet set up - over there on one of the mountain slopes which overlook the roadway leading towards the frontier.

Radu was setting his traps, no doubt, when, looking down on the road below him, he saw a sleigh coming along, driven at a rapid rate. The man who was driving was urging his horses to their best pace, but there were no bells on the horses. This would strike Radu at once as strange. Then he saw it was Ilie, wrapped in his soldier's cloak, and beside him, muffled up, was a figure the hunter knew all too well. In a moment he understood - it was an elopement! And as he gazed, spellbound, the sleigh went out of sight.

|

Radu

was setting his traps, no doubt, when, looking down on the road below him,

he saw a sleigh coming along, driven at a rapid rate. The man who was

driving was urging his horses to their best pace, but there were no bells on

the horses. This would strike Radu at once as strange. Then he saw it was

Ilie, wrapped in his soldier's cloak, and beside him, muffled up, was a

figure the hunter knew all too well.

Click on picture to enlarge it. |

There was a knock at Katinka's parents' door. I happened to be there, with some certificates to do with timber sales. Radu looked in, white and trembling.

"Where's Katinka?" "Down the village at Rosa's," was the reply.

Radu turned hurriedly away. It was only after he had been gone some time that it struck us how pale and disturbed he looked. He hurried to the house of Rosa's parents.

Katinka was not there! He rushed home, threw down his gun and traps, and unhooked a heavy revolver from the wall. Then in came his old servant. Terrified at Radu's deathly colour and trembling fingers as he loaded the revolver, she shrieked. Radu sprang over, put his hand on her mouth, and forced her backwards on to the bed, where he gagged. and bound her then out he rushed, took a horse from a neighbour's shed - unnoticed, for it was growing dusk - and rode away after the fugitive pair.

Next morning, someone looking in at the window saw the old woman tied to the bed. He raised the alarm. The door was knocked in, and the poor old lady, half dead with cold and terror, was released. Then she told, in broken words, how she came to be there.

Then we learnt that Ilie had gone and that Katinka was missing, as also were the father's sleigh and horses. We saw it all. What fearful crime had Radu committed?

There was a rush of getting out sleighs and harnessing horses and of loading guns; for it was a severe winter, and the wolves were many and fierce.

The mayor paused and gazed before him, as though looking at something afar off.

"What did you find?" asked the Belgian.

The mayor looked up from his reverie and said, very slowly:-

"We found, gentlemen, a broken sleigh, some horses' bones, a few buttons, and the blade of a sword with blood frozen on it. There were also a revolver, the handle actually gnawed away, some empty cartridges, much blood-stained snow, and three pairs of human feet."

"Radu must have caught up with the runaway pair just as a pack of wolves attacked them. Instead of killing his faithless 'mirassa' (fiancée) and her abductor, he joined them in a fierce fight for life against hopeless odds. What the moon saw that night when it rose must have been very terrible.”

Those three pairs of feet lie buried together near where they were found. The cross, as in my sketch, was put up by the fellow-villagers, and it is the custom each Christmas for the priest of the village to go out and say a mass. A little light is always kept burning, the shepherds and others keeping it supplied with oil.

|

The

cross, as in my sketch, was put up by the fellow-villagers, and it is the

custom each Christmas for the priest of the village to go out and say a

mass. A little light is always kept burning, the shepherds and others

keeping it supplied with oil. Click on picture to enlarge it. |

Main Stories from the Road page