A Word from the Founder

|

A Word from the Founder |

|

Long Riders on the Roof of the World:

Two Centuries of Tibetan Equestrian Travel

by

At the dawning of the 21st century it is standard practice to view Tibet as the beautiful mountainous homeland of spiritual Buddhist monks. Given the peaceful teachings of His Holiness, the Dalai Lama, it is easy to understand why the Tibetans are commonly associated today with the benign influences of Buddhist philosophy, for despite the illegal occupation of their homeland by the Communist Chinese, the majority of Tibetans prefer to follow the non-violent teachings of their exiled leader rather than seek revenge against their brutal occupiers.

However, what few remember today is that in spite of its peaceful reputation Tibet has the dubious honour of being the only country The Guild is aware of where Long Riders were repeatedly murdered. As this investigation of Tibetan equestrian travel history demonstrates, some of the most astonishing and dangerous horse journeys ever undertaken came to tragic conclusions in what was once known as “the hermit kingdom.”

The subject of Tibetan equestrian exploration could be said to begin with Marco Polo, who mentioned Tibet but did not visit the country on his way to Peking. In contrast to this commercial Italian traveller, the most common European visitors to Tibet were originally Catholic priests, a number of whom travelled there from China and India starting in 1624. The Capuchins even founded a mission in Lhasa in 1729.

But by the dawning of the 19th century the foreign priests had been asked to leave and the mountainous kingdom had voluntarily isolated itself from the world at large. This policy of intended segregation soon turned Tibet into a geographical mystery, a place on the map where foreigners were neither wanted nor allowed. Yet this political seclusion backfired on the country’s leaders as it ended up inspiring curious outsiders to try and penetrate the mountainous blockade. Thus for more than a century, from the 1840s until the 1940s, one of the most elusive geographical prizes on Earth was Lhasa, the country’s restricted capital.

Because they were intellectually curious, but unable to send official dignitaries, the British government in nearby India initially instituted a system of native spies, known as pundits, secretly to map the main roads in and out of Tibet. The pundits were amateur native spies who posed as commercial travellers, attaching themselves as nondescript pedestrians to caravans going into Tibet. While these men were undoubtedly brave, their academic discoveries were limited by the great secrecy they were forced to exercise in order not to be arrested and killed by the increasingly xenophobic Tibetan rulers.

By the late 19th century the mighty Russian empire authorized its most celebrated explorer to go into Tibet in search of knowledge regarding roads, trade and natural history. It was with the arrival of this Russian Long Rider that the modern age of equestrian exploration in Tibet began, for with the unannounced arrival of General Nikolay Przhevalsky in northern Tibet came the dawning of an age when mounted foreign explorers tried to penetrate the country, often illegally, for more than a hundred years.

The results of attempting to ride in Tibet, then and now, were always perilous, occasionally murderous, and are documented here for the first time.

General Nikolay Przhevalsky was Imperial Russia’s most famous explorer. He made four equestrian journeys in Central Asia, crossing the Gobi desert, the Tian Shan mountains and exploring northern Tibet before dying on expedition in today’s Kyrgyzstan. An avid naturalist, Przhevalsky is credited with making hundreds of discoveries including the wild Bactrian camel and the Przhevalsky horse, which is named after this famous Long Rider. The extraordinary life of this important equestrian explorer was recounted in the book, “The dream of Lhasa : the life of Nikolay Przhevalsky, explorer of Central Asia,” by Donald Rayfield. This account explains how the Tibetans, who were busy trying to thwart the British from entering their country in disguise from the south, were taken by surprise when the Russian general boldly penetrated their country instead from the north in 1880. Though he did not reach Lhasa, Przhevalsky made an extended equestrian investigation of the northern parts of the country.

|

General Przhevalsky is usually remembered today for discovering the wild Central Asian horse which now bears his name.

|

Unlike his Russian rival, Captain Hamilton Bower set out in 1890 to explore Tibet in secret. His expedition, which had been authorized by the British intelligence service, was beset by many difficulties including brigands, stolen horses, and suspicious Tibetans. At one point, having had his horses stolen, Bower wrote, “I had come to the conclusion that an explorer’s life is not altogether free from anxiety.” Even though he was eventually remounted, Bower was stopped by Tibetan authorities before he could reach Lhasa. The English explorer was ordered out of the country, though he was allowed to ride towards the Chinese frontier instead of being forced to retrace his route to India. Upon his return to England, Bower was awarded the Royal Geographical Society’s Founders Medal for being the first Englishman to have crossed the Tibetan plateau. In addition to the military information he gathered, this army spy had also returned with 51 rare birch-bark leaf manuscripts acquired from a native treasure hunter. Bower’s discovery of these ancient manuscripts prompted a scramble for artefacts by Europeans and led to further intrusions into Tibet. The story of Bower’s trip, “Journey Across Tibet,” will soon be republished by The Long Riders’ Guild Press.

One fact that has always struck us here at Long Riders’ HQ is how utterly different equestrian explorers are, one from the other. And yet despite their differences, they all share two common threads. They all speak “horse” and they have a need to explore the world on horseback, no matter what the cost.

As is if to prove the authenticity of this finding, and in complete opposition to the bold military men who had proceeded her, came a most unusual equestrian explorer, for of all the Long Riders who ever ventured into Tibet, none was so unprepared by her original lot in life than Isabella Bird.

No one could have foreseen the amazing life that lay ahead for this clergyman’s daughter. Of moderate means, blessed with ill-health, unwed, physically unimpressive, Isabella Bird had every reason to stay at home in the safety of her English village. She chose instead to venture out into the world, a place in the late nineteenth century still full of dangers, brigands, discomforts, and unexplored countries.

And, whenever possible, Isabella chose to see the world from the back of a horse. Bird’s journey among the Tibetans is one of her five famous equestrian trips. She had made the first documented equestrian exploration of the Hawaiian Islands, crossed the Rocky Mountains on horseback, likewise explored Japan with her saddle and went on to canter across Morocco when she was in her seventies. But of all her equestrian adventures, her ride through Tibet takes precedence. For it was here, in this vast, windswept, frozen northland that the intrepid English woman nearly met her match!

She and her little horse, Gyalo, were dashed into icy rivers. They crossed passes so high that the porters begged for mercy. They saw more adventure, and covered more miles than had ever been experienced by a female equestrian explorer, and her account of riding Among the Tibetans in 1894 provided the outside world with one of it’s first peeks at the mountain kingdom.

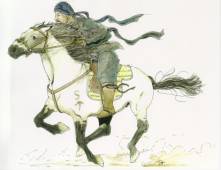

| Despite its legendary hostility, tiny Isabella Bird, and her equally diminutive mount, Gyalo, weren’t intimidated by Tibet. |

The nineteenth century can rightly claim to have seen the birth and travels of a host of brave men and women who undertook great hardships in their quest for adventure. Legendary names come to mind like Sir Richard Burton and Sir Ernest Shackleton. Yet sadly, one name is largely forgotten today, that is Henry Savage Landor.

Though Savage Landor became justly famous for making a series of trips to many outlandish and dangerous places, none of his trips aroused public sentiment like his famed journey through Tibet in 1898.

Fearing her covetous foreign neighbours in British-occupied India and Imperial China, the high Himalayan country had sealed her borders to outsiders. Thereafter a number of Europeans, including Bower, had been detected by Tibetan officials and turned back before they could reach the nation’s isolated capital at Lhasa.

With such a geographic prize at stake, Savage Landor determined to set off with a small group of native porters to reach the Tibetan capital by stealth. To say he failed would be too polite a term for what occurred next. After making his way across vast and primitive lands, the would-be equestrian explorer was detected by the Tibetans and arrested. Once they determined that the Englishman was travelling without the official sponsorship of his government, the situation turned from bad to worse.

Savage Landor and his servants were first imprisoned, then brutally tortured. At one point the explorer had his arms tied behind his back. He was then mounted on a half-wild horse, placed in an infamous “torture saddle” that had spikes sticking into his back, and forced to ride many miles, all the while being slowly torn to bits by the cruel spikes. Illustrated with hundreds of photographs and drawings, the author’s blood-chilling account of equestrian adventure, In the Forbidden Land still makes for page-turning excitement.

| After being captured by Tibetans, English Long Rider Henry Savage Landor was tortured by being forced to ride across Tibet in a spiked saddle. |

Though Sweden has had many brave sons set out to explore the world, few were as remarkable as Sven Hedin, who spent almost twenty years of his life on Asian soil.

Originally, he aspired to follow the path of other late nineteenth century Swedish explorers and engage in polar research. But an offer to serve as private teacher to the son of a man who worked in the naphtha fields of the Nobel family in Baku directed his attention to Asia. After completing his work Hedin embarked on a ride through Persia, which taught him how to endure both physical and economic hardship en route. Hedin’s Persian exploits drew him further into Asia, acquainting him with its people and history.

At the beginning of one journey that lasted three years, Hedin wrote, "The whole of Asia was open before me. I felt that I had been called to make discoveries without limits - they just waited for me in the middle of the deserts and mountain peaks. During those three years, that my journey took, my first guiding principle was to explore only such regions, where nobody else had been earlier."

During his adventurous lifetime

Hedin discovered lost cities in the Gobi desert, criss-crossed Central Asia four

times, mapped previously unexplored mountain ranges and came within a few miles

of reaching Lhasa disguised as a lowly porter in 1900. His autobiography, My Life as an Explorer

recounts his Tibetan equestrian adventures and regales the reader with almost

more adventure than one can bear to read.

|

Swedish Long Rider Sven Hedin endured a great many hardships while riding across Tibet but was eventually turned back from Lhasa by suspicious officials. |

|

Click

here

to see the world's largest collection |