Jorge Molina Salas was an Argentine gaucho who rode from Buenos Aires, Argentina to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in 1946.

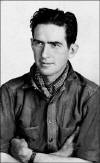

People had a hard time defining Ross Salmon, as during various parts of his colourful life he had been a pioneering aviator, decorated war hero, South American jungle cowboy, BBC TV star and a Long Rider.

His first brush with adventure came during the Second World War when he was accidentally shot down by trigger-happy Canadians preparing for the D-Day landing. After the war Ross was employed as the manager of a thirty-two square mile cattle ranch in Columbia. His duties included riding through the jungles in search of wild cattle and fighting brush fires.

But his career as a cowboy came to a crashing halt when he was involved in an airplane crash that resulted in fourteen major fractures and left Ross fighting for his life. He was saved thanks to the assistance of natives who transported him through the jungle, passing his naked, broken body from one tribe to another, until he finally reached medical attention.

The accident required Ross to spend a year recuperating in a British hospital. After he recovered he took up farming. But he still had a longing to travel, so in 1954 Ross set off on an thousand mile round-trip equestrian journey from his farm in Devon to Scotland and back. Wherever he went Ross was surrounded by children, who were enamoured by the sudden appearance of an English cowboy in their town. He was filmed riding through Piccadilly Circus, showing children how he handled his six-gun and exploring the English countryside.

His journey became the inspiration for a series of popular 1950s children’s books which included the best-selling titles Jungle Cowboy and True Jungle Stories.

The nineteenth century can rightly claim to have seen the birth and travels of a host of brave men and women who undertook great hardships in their quest for adventure. Legendary names come to mind like Sven Hedin, Sir Richard Burton and Isabella Bird. Yet sadly, one name is largely forgotten today, that is

Henry Savage Landor. Though Savage Landor became justly famous for making a series of trips to many outlandish and dangerous places, none of his trips aroused public sentiment like his famed journey through Tibet in the late 1890s. Fearing her covetous foreign neighbours in British-occupied India and Imperial China, this high Himalayan country had sealed her borders to outsiders. Thereafter a number of Europeans, including several British explorers, had been detected by Tibetan officials and turned back before they could reach the nation’s isolated capital at Lhasa. With such a geographic prize at stake, Savage Landor determined to set off with a small group of native porters to reach the Tibetan capital, Lhasa, by stealth. To say he failed would be too polite a term for what occurred next. After making his way across vast and primitive lands, the would-be explorer was detected by the Tibetans and arrested. Once they determined that the Englishman was travelling without the official sponsorship of his government, the situation turned from bad to worse. Savage Landor and his servants were first imprisoned, then brutally tortured. At one point the explorer had his arms tied behind his back. He was then mounted on a half-wild horse, placed in an infamous “torture saddle” that had spikes sticking into his back, and forced to ride many miles, all the while being slowly torn to bits by the cruel spikes. This blood-chilling account of equestrian adventure entitled In the Forbidden Land still makes for page-turning excitement.

[This image does not actually portray the Historical Long Rider or Lapis. It was chosen so as to demonstrate the uniform and type of horse used during this important journey. The Guild continues to search for a photo depicting the Long Rider and Lapis and will publish it when found.]

Otto Schoener

(left) Will Drew (centre) and Raymond Joyce were American

missionaries who went to China in the 1930s. After several years working

deep in the interior of China, the three men were informed that they had

been granted a long furlough. Instead of returning to the coast by a

traditional route, the three adventurous men decided to return to the United

States via the Gobi Desert and the Karakoram Mountains.

By the spring of 1938 the travellers had traversed the desert and arrived at Kashgar, the ancient caravan staging post in Sinkiang, western China. There they managed to attach themselves to a caravan of thirty horses which was bound from Kashgar to Srinagar, in British India.

The resulting journey lasted 47 days and required Drew, Joyce and Schoener to cross the 15,450 foot high Mintaka Pass. Commonly known as the “horse killer pass,” the travellers witnessed the bones of countless generations of horses which had died crossing that dreadful place.

In his diary Schoener recalled, “The mountain trails were very dangerous. Mountain rock slides had destroyed the narrow pathway high up on the mountain sides. Many of the wooden bridges we had to cross with our loaded animals were in bad need of repair. On the entire trip, three horses were lost because of difficult roads.”

Schoerner’s missionary website - www.schoerner.org

It was a special time, an envelope of peace in a war-weary Europe. The 1930s presented a unique opportunity for three wandering Swiss horsemen to journey across a recovering continent, a chance to see the last remnants of nineteenth century village life before it was swept away forever by the horrors of the Second World War. Hans Schwarz was just the man to lead such a mounted expedition. A lifelong horseman, Schwarz conceived of the idea of riding from the mighty frozen Alps where he lived to the steamy plains of faraway Turkey. The resulting ride can only be described as idyllic. Along with two companions, the amiable Swiss Long Rider peeked at tiny Liechtenstein, crossed Austria, explored Romania, fled Albania, endured Yugoslavia, and finally reached Turkey, then rode back again! His book, Vier Pferde, Ein Hund und Drei Soldaten, is more than just a well-written Swiss adventure tale. Schwarz's trip, and the resulting book, both took on legendary status in the German-speaking world, and inspired three generations of Swiss Long Riders to take to the saddle, including legendary equestrian travellers, Hans Jürgen and Claudia Gottet, who rode from Arabia to Switzerland on their native Arab horses.

Otto Schwarz - rode a total of 48,000 kilometres literally all over the world. The story of Otto Schwarz reads like a mounted Odyssey. As the clouds of the Second World War gathered over his native Switzerland, young Otto Schwarz was competing at Olympic level in dressage. Forced by circumstances to don the uniform of a Swiss cavalry officer, Otto patrolled the French-Swiss border on horseback for nearly five years. Those mounted adventures gave the dashing Captain Schwarz a taste for horse travel which redirected his equestrian life.

Over the course of the next sixty years, Otto Schwarz went on to journey 48,000 kilometres (30,000 miles) on horseback across five continents, making him the most well-travelled Long Rider of the 20th century. The man literally rode in a host of places including Japan, Europe, Africa and North & South America. Click here to read Otto's obituary. In his book, Reisen mit dem Pferd the famous Long Rider offers his readers a detailed supplement on how to prepare and undertake an extended equestrian journey. This important book, (written in German), belongs on the bookshelf of every student of equestrian travel.

It certainly wasn’t the fastest or easiest way to cross the United States as by 1907 the legendary Old West was fading into memory. Livery stables were failing, feed wasn’t always available and even the open-handed hospitality which had long been a blessing of the cowboy culture was being replaced by suspicion and calculation.

So when a big-city newspaper in Seattle, Washington offered young Quincy Scott a chance to become their political cartoonist, the newly-wed husband made the right choice. He suggested that he and his young bride, Ella, celebrate their honeymoon by riding from their home in Minneapolis, Minnesota to the faraway city on horseback. Mind you, it was more than two-thousand miles away across roads that were often little more than muddy tracks. But what did that matter when you were young and in love?

So it was that Ella and Quincy set off on a strangely snowy May morning. Underneath them were a couple of bargain-priced ponies, while their saddle bags didn’t hold much more than a frying pan and their dreams. Yet they never faltered, not even when the rivers flooded and the horses disappeared, or when they went hungry for another night. Regardless of a hundred unforeseen obstacles, nothing ever stopped them. Ever.

Instead they made their historic ride, and after having finally reached distant Seattle, Quincy put all their memories down on paper. He recalled how Ella had shocked the denizens of the Old West by riding astride, all the while she wore a pair of men’s army breeches underneath her rugged homemade divided skirt. He recalled how they had seen old prospectors, rugged ranchers, the fading glory of the Old West. But most of all he enshrined one of the most lovely and romantic stories ever penned by a Long Rider, a story which though never published, was later resurrected and revived by their daughter, Dorothy, in a now-rare book entitled, “Horseback Honeymoon.”

Naomi Skully was one of the three “Rangerettes” who rode from Erie, Pennsylvania to Banning, California in 1962/1963.

Sergeant Robert Seney was one of the most significant, and inspirational, North American Long Riders of the late 20th century. A lifelong horseman, Seney’s mounted career stretched from the cavalry era to the age of the modern Long Riders.

He was a member of the US cavalry when the Second World War broke out and spent the early part of the war helping to maintain a mounted guard along the Mexican border. Seney was also deployed to Italy and later served with the American Air Force. Upon his retirement from the armed services the former horse soldier worked in Olympic National Park as a professional packer.

It was during this time that the cavalry sergeant discovered the road horse that was to take him upon so many retirement era adventures.

According to Robert Seney’s son, Dick, his father’s horse, Trooper was a big cold blooded grey gelding. Mounted on the grey Trooper, Seney made a series of equestrian journeys through the United States, the effect of which inspired the next generation of American equestrian travellers to emulate this great and generous horseman.

Together Seney and Trooper explored California’s back country trails and also rode the Pacific Crest Trail three times. In 1976 the mounted patriot set out to explore his homeland, a journey which saw Seney and Trooper making an extended journey to various parts of the United States. During that trip, and many subsequent adventures, nothing stopped the old cavalryman except truly bad weather.

The sergeant turned Long Rider made six journeys between 1967 and 1980. The shortest journey was 2,000 miles and the longest was 9,000 miles. His combined travels through all 48 states exceeded 24,000 miles in the saddle.

Sergeant Robert Seney, last of the American cavalry Long Riders, died in 2001 in Arizona, but not before leaving many stories of his travels. The Guild has published a summary of Bob’s wisdom entitled Long Distance Travel on Horseback.

One of the most unusual Historical Long Riders came from the tiny mountain kingdom of Gahrwal adjacent to Nepal. Giyan Sing was one of these hardy mountaineers who had enlisted to serve in the British army in India. When Lieutenant Percy Etherton asked for a volunteer to accompany him in 1909 on a 4,000 mile ride from Kashmir, north to Gilgit, across the dangerous Pamir mountain range, through Chinese Turkistan and Mongolia, the intrepid Sing accepted the challenge. His decision was made all the more extraordinary considering the fact that Sing had no previous equestrian experience. Nevertheless the small equestrian traveller rode alongside Etherton throughout their lengthy journey. Upon reaching Yarkand, the weary Long Riders were invited to a feast hosted by the local Chinese governor. Though they were thousands of miles from Peking, the governor nevertheless produced a plethora of tasty dishes including pigeon’s eggs preserved in chalk, lotus seeds, stag’s tendons and sea slugs. The ride turned deadly when Sing and Etherton rode into Siberia during the winter of 1910. The cold was simply appalling, with the temperature sinking to 46 degrees below zero, when Etherton suffered from frostbite. When they remarked on the cold, a local Siberian told the equestrian explorers that though the Czar might rule all Russia, it was King Frost who ruled Siberia. Having ridden four thousand miles with Etherton, the young Gahrwali tribesman completed the journey to England by train and ship, reaching London fifteen months after first stepping into the saddle.

“Medicus”

was the pen name adopted by Daniel Denison Slade, an American physician, born in

Boston, Massachusetts, 10 May, 1823. After graduating from Harvard in 1844,

Slade went abroad for the purpose of higher studies, and on his return in 1852

he settled in practice in Boston.

During the civil war he was appointed one of the inspectors of hospitals under the United States sanitary commission.

Despite his medical success, Dr. Slade gradually relinquished his medical profession in favor of literary and horticultural pursuits, and in 1870 was chosen professor of applied zoology in Harvard, which chair he held for twelve years.

In 1884 he was appointed assistant in the Museum of comparative zoology and lecturer on comparative osteology in Harvard.

Though he is best remembered for his prize winning medical books, Slade also wrote this rare account of equestrian travel. Like his fellow New Englander, Captain John Codman, Dr. Slade was an advocate of the physical benefits of what was then termed equestrianopathy. “No exercise can compare with that of horseback riding,” he wrote.

His short booklet, “Twelve Days in the Saddle,” recalls how in 1883 Slade and his daughters rode through primeval forests, alongside rushing rivers and ventured into the still unspoiled valleys of Connecticut, Vermont and Massachusetts. Yet in addition to this lovely story, Slade was wise enough to provide would-be equestrian travellers with a list of tips on how to make a successful journey. The “Maxims” provided by the good doctor still hold true today.

An English immigrant, J. Smeaton Chase

(1864-1923) came to California in 1890 where he pursued a career as one of

the state’s earliest social workers. Yet he never allowed his career to

interfere with the life-long pursuit of his twin passions, equestrian travel

and botany. Though Chase made many various horse trips throughout the

American West, his book

California Coast Trails describes his most

famous journey, from Mexico to Oregon along the coast of California in 1910. The

amateur scientist doesn’t merely ride along, he treats us to a treasure

trove of observations, commenting on subjects as diverse as the architecture

of the Spanish Missions, the hospitality of the people, and the beauties of

a fabled countryside in the last days of its pristine natural glory. While

Chase regales the reader with adventures, such as rescuing his horse from

quicksand, the book is far more than a mere account of an equestrian

exploration.

Then in 1916 Chase mounted up and rode into the Mojave Desert to undertake the longest equestrian study of its kind in modern history. The book of this journey, California Desert Trails, is one man’s love affair with the Mojave Desert.

William Somerset Maugham (1874 – 1965) was an

English playwright, novelist and short story writer. He was among the most

popular writers of his era and, reputedly, the highest paid author during

the 1930s. His most famous books include "Of Human Bondage" and "The Razor's

Edge." Yet prior to becoming a famous author, the twenty-three year old

Englishman decided to seek adventure overseas. One of his earliest works

dealt with the equestrian journey he made thorough Spain in 1898. In "The

Land of the Blessed Virgin - Impressions of Andalusia" Maugham recounted his

ride from Sevilla to Carmona and back. This accurate account captured the

look and feel of a country before the onset of a deadly civil war and

industrialization changed it forever.

Click here to read an excerpt from Impressions of Andalusia.

Edith Somerville and Violet Martin were the two fun-loving, hard-riding, co-writing female cousins who penned a total of fourteen books, including their immortal classic, Some Experiences of an Irish R. M. While readers of that generation would have recognised the names of the co-authors' pseudonyms, “Martin Ross” and “E. Œ. Somerville,” few knew that the books were actually the pen names of these light-hearted Irish Long Riders. Their most famous equestrian work was entitled Beggars on Horseback. This delightful book recalls how the high-spirited young ladies decided to tour North Wales on horseback. Finding suitable horses was their first task: even in 1894 this was no easy matter, especially when they explained why they needed them: “We were conscious of social shrinkage as the work for which we required the ponies was explained; a fortnight’s road work in Wales, with the proviso that the animals would have to carry packs, held a suggestion of bagmen, not to say tinkers.” They were both avid horsewomen, and in due course they hired two ponies who have pride of place in this enchanting tale.

Marcelino Soulé

made one of the most important equestrian journeys in the 20th

century but then the story of Argentina’s astonishing Long Rider vanished

for decades.

Millions of people ride horses. Only a few become Long Riders. What is truly rare is to discover a "lost" Long Rider of great historical importance. During his journey across Argentina, Agustín María Mayer made such a discovery. While riding through the small town of Bolivar, he was told about Marcelino Soulé. To understand the significance of this Argentine Long Rider you must first appreciate the man who inspired him.

In 1925 Aimé Tschiffely set out to ride 10,000 miles alone from Buenos Aires to New York City. For the next three years the Swiss Long Rider and his two Criollo geldings, Mancha and Gato, survived a litany of hardships unequalled in equestrian travel. Tschiffely's original plan was to ride from Buenos Aires to California, then across the USA to the Atlantic. Yet once he crossed into America Tschiffely quickly changed his mind when the driver of a car deliberately hit him and Mancha. Tschiffely felt that the American drivers were so dangerous that he shortened his journey and turned his back on California. Instead, Tschiffely rode to Washington DC and then on to New York.

For nearly a century it has been a common belief that Tschiffely's original plan was never completed. We now know that Marcelino Soulé rode from South America to North America - and then east to west across the United States, making it one of the most important equestrian journeys of the 20th century!

The story of Soulé's ride has been rescued from the shadows by two ardent Argentines. Senor Santos Vega preserved a copy of Soulé’s rare book, "Cutting the Continent." And historian Matias Gabriel Terrara has spent years collecting information and photos connected to Marcelino Soulé's journey.

Thanks to their work, the Guild has confirmed that Soulé began his ride in his hometown of Bolivar on July 27, 1938. More than a thousand people gathered in the plaza to say goodbye to the Long Rider and his Criollo horses, Argentino and Bolivar. The journey went well until the trio arrived in Columbia, where Soulé became critically ill with malaria. After being hospitalized for 21 days, he discovered that his horse Bolivar had died. Refusing to quit, Soulé continued north. He is supposed to have swum across the Panama Canal with his horse. In Mexico he was attacked by bandits and Argentino was stolen. Having obtained another mount, the determined Argentine continued. He arrived in Washington DC on February 9, 1941, met President Roosevelt, and then rode on to New York City. After resting, Soulé rode to Chicago and then on to San Francisco. He died at the age of 44 in a car accident in Argentina.

Matias Gabriel Terrara has created an extensive website which provides details about Soulé’s remarkable journey. The Guild would like to thank Matias and Senor Vega for ensuring that the memory of this great Argentine Long Rider was preserved for posterity.

Freya Stark - Dame Freya Madeleine Stark was a British travel writer, who was not only one of the first Western women to travel through the Arabian Deserts, she also explored Turkey, Nepal and the Pamir mountains on horseback. The intrepid lady Long Rider believed there were two kinds of people in the world, villagers and nomads.

“There can be no happiness if the things we believe in are different from the things we do,” she wrote, before setting out to ride alone across the Turkish plateaux to the distant Tigris River. Along the way she journeyed from Lake Van through desolate mountains, during which time she encountered Turkish governors, mad men, villagers and policemen, all of whom were baffled at her unhurried manner of travel. Never a quitter, the woman known as the “poet of travel,” climbed the notorious Annapurna mountain at the age of 86 and lived to be a hundred.

Edward Percy Stebbing - Like many of his English generation, Edward Stebbing was

deeply involved, and affected, by the First World War. Though he inspected

the Serbian front, his most important war time experience occurred in

Russia, which he visited in 1917 between the fall of the Czar and the rise

of the Bolsheviks. A keen political observer, Stebbing correctly prophesized

that Germany viewed Russia as a potential bread basket and that it was in

England’s best interests to protect her ally. “The object is to save the

Russians from the Germans, for if we fail now the war will have to be fought

out again in the future,” Stebbing wrote. His warning proved to be all too

true, as Hitler later invaded Russia so as to seize its vast resources.

Stebbing was no mere political columnist. He spent many years living in India, where he served in Forestry Service. Once again his observational skills were employed, this time to write a book about the insect life of the Indian subcontinent. Upon returning to Great Britain, he became a professor at the University of Edinburgh. During his forty-year career, he led one of the earliest efforts to study the danger of desertification presented by the encroaching Sahara.

Yet it was thanks to Stebbing’s organization and participation in the largest mass equestrian journey in English history which led to him being named as a Historical Long Rider.

While doing research for The Guild’s Horse Travel Handbook, the Guild recovered a rare book entitled Cross Country Riding. Written by Stebbing in 1938, there are less than half a dozen copies of the book now in existence. In addition to sharing the wisdom gained from years of riding in both India and England, the author made the startling announcement that he had been inspired to write his book because of the immense success of “The Long Distance Ride.” A diligent hunt through a great many archives finally located a copy of Stebbing’s article wherein he described how hundreds of equestrians rode from all points of England so as to gather in a grand ceremony in southern Britain.

Dated August, 1937, the story described how a host of British horse riders set out from eight starting points, bound for a central meeting place at Eastbourne. Not only were the editors of the sponsoring magazine surprised that more than twice as many people as expected decided to ride across Southern England, they also reported that one contestant came from as far away as Norway. Nor was an age a factor, as the oldest rider was 76 and the youngest only 11 years old.

What Long Rider Stebbing’s terrific article reveals is that there are unexpected lessons to be learned when ring riders venture out of doors, be it in 1937 or more than seventy years later. Not only do they develop their courage, more importantly, they realize that riding isn’t merely about detail, it is about individual accomplishment. Regardless of what year the calendar says, equestrians in search of the “centaur moment” are learning that it isn’t “Thou Must” but rather “This Is.”

History proves that more often than not Long

Riders are made, not born to a life of equestrian exploration. John Lloyd

Stephens (1805-1852) is one such example.

Like many another young man Stephens followed his wealthy parents' wishes. In his case he studied law at a prestigious American university. But a life spent indoors arguing about legalities was not as appealing as exploring the world. In 1834 Stephens bid his family adieu and set sail for Europe.

For the next four years his restless spirit drove him from one country to the next. Western Europe wasn’t enough. He had to go on to Poland and Russia. Then he headed south to Greece. Having come so far he saw no reason to halt his progress, so ventured on to Turkey and the Holy Land before finally coming to a halt in Egypt.

This initial burst of energy resulted in Stephens writing two popular travel books, after which he seemed destined to return to a life of legal boredom. Then fate stepped in.

President Martin Van Buren asked Stephens to act as an agent of the United States government and to undertake a confidential diplomatic mission to Central America.

Thus in 1838 Stephens arrived in what was then the colony of British Honduras and is today’s modern Belize. Though he had been delegated to carry on diplomatic research and high-level meetings with various government officials, the indefatigable Stephens wasn’t about to neglect his love of travel. Accompanied by an artist named Frederick Catherwood, the two men obtained horses and set off into the vast jungle of the Yucatan Peninsula.

Stephens’ curiosity had been alerted to the supposed existence of mysterious ruined cities deep in the jungle. He later wrote, “During our short sojourn in Yucatan, we received vague, but, at the same time, reliable intelligence of the existence of numerous and extensive cities, desolate and in ruins.”

What Stephens and Catherwood discovered shocked the world.

“In five minutes after leaving the hacienda, we passed between two mounds of ruins, and, from time to time having glimpses of other vestiges in the woods, in twenty minutes we came to a mound about thirty feet high, on the top of which was a ruined building. Here we dismounted, tied our horses, and ascended the mound.”

Under the jungle creepers Stephens discovered a lost temple of the Mayans, its ancient walls covered in vivid murals painted in bright colours of red, green, yellow, and blue. But this was only the first of many such discoveries. They were the first explorers to investigate the Mayan ruins at Copán. They found the lost “Temple of the Sun.” Before their jungle journey was over they had located and visited 44 Mayan sites.

After having mapped the locations, they returned to the United States whereupon Stephens wrote one of the classics of travel literature. The lawyer turned jungle Long Rider’s book, Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatan became an instant sensation upon its publication. Catherwood’s illustrations entranced the multitudes. But Stephens’ honest writing style riveted the readers.

Critics have long agreed that Stephens never used any tricks in his writing style. He recited the story in a dry, matter of fact manner as if he were merely reciting a tale told to companions sitting round the campfire. But it was the very calmness of the writer that made his tale all the more astonishing. Whereas some would be tempted to boast or brag, Stephens eschewed any traces of trickery. He preferred to quietly recount how he had ridden through the jungle and then found some of the world’s most remarkable architectural treasures.

Today Stephens’ book and his journey in Central America and Yucatan are considered to have created the richest contribution ever made by any one man to the subject of American Antiquities.

But it would be a mistake to think that Stephens’ book is simply an account of Mayan priests and Sun Temples, for lodged within his pages is the first account of a Long Rider encountering one of the most savage scourges of the jungle, the notorious, blood-sucking garrapatas.

Generations of Long Riders have since written about their pain-filled encounters with these insects, which are so tiny that they resemble dots of red sand. But size doesn’t matter. When they covered German Long Rider Günter Wamser, he wrote about how they bit and devoured him to the point of madness. “I thought I would tear my skin off,” he later wrote.

Yet it was Stephens who first found and was attacked by this curse of the Mayan jungle.

In his book, Stephens’ wrote, “Because of my interest in the work, I did not realize that thousands of garrapatas were crawling over me. These insects are the scourge of Yucatan, and altogether they were a more constant source of annoyance and suffering than any we encountered in the country. I had seen something of them in Central America, but at a different season, when the hot sun had killed off the immensity of their numbers, and those left had attained such a size that a single one could easily be seen and picked off. These, in colour, size, and numbers, were like grains of sand. They disperse themselves all over the body, get into the seams of the clothes, and, like the insect known among us as the tick, bury themselves in the flesh, causing an irritation that is almost intolerable. The only way to get rid of them effectually is by changing all the clothes. It was the first time I had ever had them upon me in such profusion, and their presence disturbed most materially the equanimity with which I examined the paintings. In fact I did not remain long on the ground.”

Having escaped the clutches of the dreaded garrapatas, Stephens returned to Central America in 1849. This time his attention was focused on the creation of a canal across the jungles of Panama. But even a man of such unconquerable energy and perseverance can push his luck too far. It was while riding and exploring that he was severely injured when his mule fell on him. In violent pain from a severe back injury, and suffering from various types of tropical fever, Stephens was brought back to New York, where he soon died from his wounds.

Even in the Age of Adventure, there were few men to equal Thomas Stevens! He scouted for the famous African explorer, Henry Morton Stanley. Then in 1866 the American reporter proceeded to pedal a penny-farthing bicycle around the world, seeing the sights in Europe, out-racing a mob in Persia, and baffling the Japanese in Yokohama. No sooner had Stevens returned from his four-year bicycle marathon than he was hired by a New York newspaper to go to Russia on a special assignment. Only this time Stevens was ordered to travel through the heart of the Czar’s vast domain on horseback! Though the intrepid traveler had already lived through dozens of dangers, Russia presented new challenges. Mounted on his faithful horse, Texas, Stevens crossed the Steppes in search of adventure. Cantering across the pages of Through Russia on a Mustang is a cast of nineteenth century Russian misfits, peasants, aristocrats—and even famed Cossack Long Rider Dmitry Peshkov. This exciting equestrian tale is illustrated with photographs taken by Stevens during his historic trip.

At a time when polite Victorian society severely curtailed a woman’s activities, famous female adventurer Ella Sykes risked her life on a daily basis. Religious fanatics failed to frighten her. Forsaken, hostile deserts never slowed her horse-bound progress. Instead Ella Sykes rode side-saddle 2,000 miles across Persia, a country few European woman had ever visited. Mind you, she travelled in style, accompanied by her Swiss maid and 50 camels loaded with china, crystal, linens and fine wine.

In her day Sykes was considered one of the bravest women alive. Today her remarkable story, replete with rajas and rogues, camels and caravans, is all but forgotten.

Illustrated with photographs taken by Sykes, Through Persia on a Side-Saddle is a rare glimpse into a lost and romantic portion of the nineteenth century world!